Ketchum, Idaho–Ernest Hemingway was found dead of a shotgun wound in the head at his home here today. His wife, Mary, said that he had killed himself accidentally while cleaning the weapon. Mr. Hemingway, whose writings won him a Nobel Prize and a Pulitzer Prize, would have been 62 years old July 21.

Ketchum, Idaho–Ernest Hemingway was found dead of a shotgun wound in the head at his home here today. His wife, Mary, said that he had killed himself accidentally while cleaning the weapon. Mr. Hemingway, whose writings won him a Nobel Prize and a Pulitzer Prize, would have been 62 years old July 21.

Frank Hewitt, the Blaine County Sheriff, said after a preliminary investigation that the death “looks like an accident.” He said, “There is no evidence of foul play.”

The body of the bearded, barrel-chested writer, clad in a robe and pajamas, was found by his wife in the foyer of their modern concrete house. A double-barreled, 12-gauge shotgun lay beside him with one chamber discharged.

New York Times, July 3, 1961

———————

“Parker, Parker, Parker … remind me again what it is about you that I find so insufferably annoying?”

“My effortless good looks, sir?”

“Good lord no, man. That’s nothing but a fortuitous roll of the genetic dice.”

“Perhaps my razor-sharp intellect then?”

“I should think that hardly merits a response.”

“Then surely it must be my boundless tenacity, sir.”

“Yes, yes. That’s it! Your damnable tenacity.” Weaverling looked up from behind his desk where, like most days, he sat in his wheelchair, poring over a crusty volume of Balzac with an enormous magnifying glass. “To which point, I could have sworn we agreed only two evenings ago that you were going to leave this Hemingway business alone once and for all. Only this morning, over breakfast, I receive a phone call from a book dealer in London indicating that, sure enough, Parker is back on the trail again, as doggedly as ever. Tell me, my friend, was it, in fact, you who I struck this agreement with, or have you a heretofore unseen twin brother you send out to participate in conversations whose outcomes you foresee and don’t much care for?”

Sure enough, as Weaverling’s discerning eye and sardonic wit had deduced, I’d been utterly unable to leave the Hemingway matter alone, not for one moment in the two days since the agreement to which he now referred, nor, for that matter, during any of the sixty odd days since the nefarious incident had occurred. Indeed, in the most recent forty-eight hours I had slept not a moment, despite numerous futile attempts. Having exhausted myself in the preceding days interviewing everyone who might have a modicum of expertise to contribute to the matter and generally striving to make sense of the whole grim affair, my nights were then spent in fits of involuntary cogitation, running it all through my head for what seemed the thousandth time. Somewhere, I told myself, in all this morass of information, there lies concealed a wedge which, if I could but discern it, might be forced between the cracks of this torturous mystery and in so doing reveal at last the truth of the matter. Except that Weaverling had, only two days ago, suddenly and peremptorily decided to terminate the investigation. And Weaverling is the man I work for. Bit of a conundrum, that.

It had, as I stated, been two months since the fateful night of the disappearance. Since then Weaverling had been in more or less constant contact with Philip Rasmussen, head of the investigations arm at Lloyds, concerning a claim which, if honored, promised to be both highly unusual and extraordinarily expensive. Lloyds, of course, had a world-renowned business insuring things—quite valuable things typically—but they relied on small contractor firms for certain niche forms of expertise, one of which was to ensure the veracity of arcane collectibles—everything from numismatic and philatelic pieces to fine wines and jewelry. Which is where Weaverling and I came into the picture. We were in the business of authenticating rare books and manuscripts, many of which were insured by Lloyds and one particularly important example of which had gone missing on that night two months hence, causing its owner—my boss—to file a claim against a policy whose face value of twenty-five million dollars would easily make it the most ever paid out for the loss of a single volume. One can imagine Rasmussen’s incredulity upon hearing that his principal rare book consultant was filing a claim for the loss of his own most prized edition. Needless to say, our enduring relationship with Rasmussen notwithstanding, Lloyds was less than keen to pay on the policy, at least not without performing a suitable amount of due diligence to determine not only the circumstances surrounding the loss, but also the authenticity of the original item, this latter of which would, without question, have been agreed upon at the time of the policy being written (including the provision of considerable provenance), but which nonetheless would come up again as an issue prior to any settlements being rendered.

Weaverling and I had been in this business for nigh on twenty years and, recondite details aside, it had proven to be an altogether fascinating endeavor, particularly for bibliophiles such as us. I had met the man in college—the young graduate student struggling to grasp the nuances of ancient versus modern Italian as manifest in original editions of Dante, and he, cursed with a lifetime of physical immobility, yet nevertheless renowned as the nation’s preeminent expert on ancient Western texts. Even in those halcyon days, I had possessed what I regarded as a respectable collection of first editions—respectable, that is, until the day I was invited for the first time to Weaverling’s home to participate in a small colloquium on the identification of original editions by their paper (the final evaluation of which required that students successfully distinguish various antiquated volumes by their odor alone).

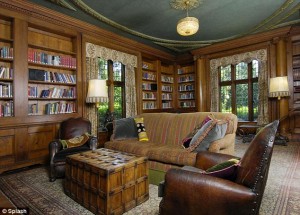

I remember, like it was yesterday, the first time I walked into Weaverling’s study. It was as though the lost libraries of Alexandria had appeared in their entirety here in a single room in the suburbs of eastern Connecticut. Easily ten thousand volumes, many of them extraordinarily rare first printings, all in remarkable condition and assiduously arranged on walnut shelves of such polished beauty and warmth as I had never before imagined, much less experienced. They were all there, every important literary achievement of the past three centuries, and many more ancient even than that. It rendered irrelevant, possibly pitiful, at a stroke, the feeble five-hundred-volume collection back in my apartment. I made up my mind, then and there, that I would work for the man who had amassed such an astonishing collection.

Now, twenty years on, I think of Weaverling’s books as very nearly my own. I certainly spend every bit as much time in their presence as he does. The collection is a source of pride, the library a sanctuary in chaotic times. It has been visited by more academic researchers than I can recall. And it has played host to countless discussions and debates—sometimes collegial, sometimes passionate—about the role that literature has played in the past five hundred years of human history. But perhaps the strangest regular gathering to take place in Weaverling’s library is what has come to be known as the Vendetta Society.

The Society is an enthusiastic but ultimately harmless collection of novelists—some reasonably well known, others less so—who gather in the library every couple of months to sip brandy, debate bibliophilic arcana among Weaverling’s rare books, and engage in a creative exercise that is, at once, macabre and fascinating. The objective is for one member, identified in advance so as to afford him an opportunity to think through the matter ahead of time, to describe to the assembled body the grim details of how he would assassinate some famous figure from history. As all of the members are writers, the goal is to contrive a convincing scheme that will not only result in the demise of the targeted individual (which tradition requires be a genuine human rather than a fictitious one), but also allow the perpetrator to escape unharmed and undetected. Most importantly, however, the scheme, once presented, must withstand the withering scrutiny of the remaining members, a creative and discerning lot indeed. Top marks are awarded for not only the most narratively elaborate and efficacious proposals, but also those that target individuals most likely to be well protected—presidents, despots, and the like.

Society members have, over the fifteen or so years of the group’s existence, concocted the demise of politicians, actors, scientists, and even the occasional academician, the circumstances of this latter category frequently having to do with some personal vendetta that it behooves the perpetrator to keep secret from society in general, but which is perfectly fair game in Weaverling’s library, all such conversations occurring in that august setting understood to be held with the utmost discretion. It was at just such a meeting, now two months past, that the subject of which I write had first been raised. It was Patterson’s turn at the lectern, and he had offered the surprising choice of Ernest Hemingway as the victim of his grim creativity. Patterson was a magnificent writer of essays but a shy man and easily intimidated by others.

“Good God why, man?” objected a little-known but frequently obstreperous member of the group named Childers, challenging from the outset and in a most uncharacteristic manner the speaker’s choice of target. One of the understood but unspoken rules of the game was that presenters were free to select any individual whatsoever, from the most despised tyrant to the humblest housewife. It was the creativity of the scheme that was up for scrutiny rather than the choice of target. But no one could recall anyone having before chosen a fellow author as target, and it was likely this that set off the unprecedented harangue.

“Well…” Patterson rejoined, momentarily taken aback by the unexpected and too-early challenge, “Hemingway was a singularly … durable chap and would, no doubt, have been well protected, particularly later in life as his fame reached its apex. Besides which, he was more than competent with firearms and certainly capable of handling himself.”

“Competent indeed,” replied Patterson’s interlocutor. “Competent enough to leave his brains all over the foyer wall. The man was unhinged and scarcely required assistance from any of us to meet his maker.”

“Honestly, Childers,” intoned Weaverling at this point. “Let the man get on with the telling of his fiendish plot, else we’ll be here ‘til sunrise.”

Patterson nodded slightly in acknowledgement of Weaverling’s defense and Childers harrumphed before sitting back heavily in his chair. But no sooner had Patterson drawn a breath and begun to rejoin his narrative when another voice rose from adjacent the fireplace. A tall bearded man, chairman of the local university English department, held in his hand a thin blue volume he’d taken down from a shelf in Weaverling’s Hemingway section. He opened the book carefully, thumbing through the pages as he spoke without looking up.

“Tell me, Weaverling, do you think it’s true what they say about the blood volume?”

A hush fell over the room as Patterson looked first at the professor and then turned to face his host.

“Hedges, for the love of God, you can derail a perfectly good conversation like no one I know,” Weaverling said without hesitation. “Why do you bring up such patent nonsense when we’re on the very verge of sending the famous novelist to his final reward?”

“Apologies to our distinguished presenter, Hedges said, nodding condescendingly in Patterson’s direction, “I simply couldn’t help but wonder if the most knowledgeable bibliophile in all of New England might proffer an opinion as to the veracity of what is regarded as the rarest of twentieth century literary collectibles.”

It occurred to me to wonder, as I listened to this exchange, how many of the dozen or so men gathered in the library actually knew the legend of the blood edition. No matter, though, I quickly realized, for if Weaverling had any weakness, it was his penchant for demonstrating an encyclopedic knowledge of rare books, whether genuine or mythical.

“It’s surpassingly rude of you to interrupt poor Patterson here with such a query, Professor Hedges, but since you’ve opened the floodgates, as it were, I’m sure our esteemed presenter won’t mind too terribly if I digress for a moment to offer an opinion on the matter you raise. It may, at any rate, add a bit more color to his forthcoming and no doubt compelling description.” Weaverling paused a moment to refill his brandy snifter and to allow a sufficient degree of anticipation to gather in the room.”

“For many years,” he began, pausing for an evaluative sip, “as our distinguished academician here is well aware, rumors have swirled amongst bibliophiles as to the existence of a profoundly rare copy of The Old Man and the Sea. While the first printing itself is rare enough—fifty thousand copies in the original run, of which only a small fraction exist today, excluding, of course, the LIFE magazine printing which predates the initial issue of the book by a few weeks—the volume in question is truly one of a kind. Professor, if you’d be so kind…”

Weaverling extended his hand toward Hedges, requesting that his copy of the novel in question be handed over. The professor closed the delicate volume and laid it gingerly on the desk. Weaverling took up the book and considered it as he continued.

“Every author, of course, keeps copies of his own books at home, and Hemingway, being no exception, had a few copies of this thin novella lying around the house in Ketchum, Idaho. Also, like any successful writer, several of these copies bore autographs and inscriptions intended for various friends, relatives, and business associates. It is said that he had inscribed a copy for Mary and that this copy was lying on an end table in the foyer of their home on that tragic night when Hemingway put the shotgun in his mouth. As a consequence of the novel lying face-up on the end table and being located directly behind Hemingway, the book jacket and text block edges are said to be decorated, if you’ll forgive the expression, with numerous drops of the man’s own blood.”

Weaverling paused one more time, partly to sip again from his brandy, and partly for enhanced dramatic effect.

“Needless to say, were such a volume to actually exist, it would be a priceless collectible. Only imagine the great author’s most famous novel, inscribed to his loving wife, and besmirched with the blood from the very brain that composed the work.”

As Weaverling waxed on about the legendary volume, I sat silent and innocuous at one end of the library’s great sofa. I had attended most Society meetings, but I rarely offered opinions on the schemes being discussed. Reticent by nature, I served as a foil to Weaverling’s effusiveness. Consulting the library clock, I noted that the hour was approaching nine, at which time I had previously alerted Weaverling I would quietly depart for a prior engagement, leaving he and his colleagues to imagine an alternative ending for the author. My errand was, though, a brief one, and I expected to return to the library around eleven in order to continue a bit of current research, by which time the gathering would have dispersed, the old man would have retired for the evening, and I would have the library to myself. In the event, I was slightly delayed in my return and did not make it back until nearly eleven thirty. All was utterly quiet as I entered the darkened room, as was frequently the case. Weaverling was a morning person and generally in his bedroom long before midnight. I, conversely, was of little practical value before noon and performed my best work in the darkest hours of the night. More than a little exhilarated by my walk in the brisk late night air, I was prepared as I entered for a productive night of research. I was not, however, prepared for what greeted me as I walked back into Weaverling’s library. The great man was still seated in his wheelchair, but was face-down upon the blotter, itself soaked through with the remains of the upset brandy bottle, which lay on its side near the corner of the desk.

I rushed quickly to the old man’s side, simply to confirm that he was in no worse condition than passed out, which diagnosis turned out, mercifully, to be the case. He lay sonorously snoring but unresponsive to my repeated speaking of his name. Weaverling was in no way disposed to over-imbibing and had never in my experience been found in so ignominious a position as he now occupied. I was at something of a loss as to whether to attempt to move the man to his bedroom or leave him where he sat. After brief consideration, I opted for the former and lifted the unresponsive man’s head and shoulders so as to place him more securely in the wheelchair before moving him upstairs. It was at this point that I spied the small hand-written note in the center of the desk where Weaverling’s head had been previously covering it. The note, like the blotter, was soaked through with brandy. It was, though, still quite legible, its contents both terse and taunting, and I could not restrain myself from reading.

“Such a priceless thing deserves better than to be locked away in an old man’s safe.”

I could not say with certainty what the note referred to but I had a passingly good idea, though I would not be able to validate my hunch until I had taken care of Weaverling. This I promptly did, moving my still-snoring boss and mentor upstairs and, with no small amount of effort, getting him into his bed, albeit still clothed as he had been in the library. I then rushed back downstairs to see if things were in as bad a shape as I imagined them to be. They were.

The existence of Weaverling’s library safe was, if not well-known, at least widely imagined and frequently discussed, albeit behind its owner’s back. Directly behind his desk, hidden under a paneled walnut wall that slid to one side with a modest tug on a subtly hidden lever, stood a massive steel safe nearly as tall as the room and wider than the desk. It was here, I had discovered only after working with the man for two years, that Weaverling kept his real collection, his most prized literary possessions, items most did not know even existed, much less that they lay ensconced in a humble safe in eastern Connecticut. He had hand-written poems by Longfellow and Frost, unpublished manuscripts by Faulkner, Steinbeck, and Fitzgerald. He had unblemished editions of Chaucer and Dante. And he had the Hemingway blood volume he had so ably described and as handily dismissed as myth earlier that evening. Or at least he had had it until now, for when I opened the safe to confirm my hunch, I saw to my horror that the space occupied by the book and its protective case was empty. Nothing else in the safe had been touched.

By nine the following morning the police had come and gone and Weaverling was back at his desk, nursing a nasty headache from whatever had been snuck into his brandy the previous night. We tossed ideas about. How had it happened? How had the thief known about the safe, much less the specifics of what was inside? And how on earth had he gotten into a safe that opens only in response to Weaverling’s thumbprint? Only it then occurred to us, as Weaverling sat unconsciously rubbing at his wrist, that a thoroughly drugged man would have offered precious little resistance to his hand being twisted into the necessary position against a thumbprint reader. One small piece of the mystery solved, but no clue at all as to who might have perpetrated such a thing.

“It’s such a unique volume,” Weaverling said. “How can someone possibly hope to sell it without being discovered?”

“Is it possible he doesn’t mean to sell it? ”I replied. “Might he be a collector like yourself?”

Weaverling considered this possibility silently, offering only a look that suggested perhaps mild offense at the comparison. “Albeit a collector,” I quickly clarified, “with distinctly, uh, nontraditional methods of acquisition.”

“Even if it were a black market sale, I should think the buyer would insist on having it authenticated before they would make a legitimate offer,” I continued. “It’s odd on so many levels. Why take only the Hemingway? Why leave behind so many other priceless treasures?”

“And how, for that matter, did they manage to knock out only me when everyone was drinking from the same brandy bottle?” Weaverling wondered aloud.

I pondered this aspect of the mystery for a moment. “There were a dozen men in the room last night. I find it surpassingly strange that the most valuable Hemingway volume in existence was pilfered on precisely the night that Patterson was conspiring to assassinate the man, even if only fictitiously. Can that possibly be coincidence, sir?”

“And what of Hedges?” he replied ignoring my admittedly rhetorical question. “The man practically taunted me into admitting the existence of the book. Surely he somehow knew of it.”

“Well, sir, the police have the brandy bottle and your glass for examination. I suspect they will find that whatever sedative the miscreant employed was administered to your glass and not to the bottle.”

“A possibility. Imagine it, though, Parker. Suppose they were all in league together. It would have been a simple matter to slip the sedative into the brandy and then instruct everyone to surreptitiously hold their glasses and not drink.”

“Hard to envision such a far-ranging conspiracy, sir. You’ve known some of these men for decades. Still, it is an extraordinarily valuable item. It’s a bizarre thing—bizarre indeed.” I shook my head ruefully. “Thank goodness you have the volume insured.”

“Oh, indeed, Parker. Indeed. Everything in the library, both in the safe and on the shelves is covered against all manner of nefarious deeds and unfortunate accidents. I should, of course, dearly like to retrieve the Hemingway, but if we do not, there’ll be quite a good deal of money to comfort us.”

“Lloyd’s will no doubt put up a bit of a fuss.”

“To be sure, my friend. But in the end, they have little choice. A theft is a theft, yes?”

Some variation of this conversation went on for many days thereafter, during which time the authorities, either through their own zealousness or at the behest of Lloyd’s, took time to interview each of the men who attended the Society meeting on that fateful evening, focusing special attention on Patterson and Hedges, both for reasons already stated. At Weaverling’s request, the police did not divulge to the interviewees the precise nature of the pilfered item, explaining only that something of tremendous value had gone missing. Weaverling cooperated as best he could, demonstrating the opening of the safe, providing access to his liquor cabinet, and explaining the many nuances of the purloined volume, whose copious provenance, including forensic certification of the blood marks, was packaged with the book and so was missing as well. This continued for nearly two months, during which time not only were the police assiduous in their investigation, but I took it upon myself to dive into the matter as well, reestablishing contact with as many rare book agents as were contained in our considerable reference list. The goal of these efforts was simply to determine if there had been any unusual activity in Hemingway rarities in recent days. I, of course, took great pains to keep my inquiries of a general nature to avoid revealing the existence of the blood volume.

Only then had arrived that day and the conversation described at the outset of this account, during which Weaverling restated his earlier exhortation that I ought to leave the matter to the authorities and, instead, get on with various and sundry other pressing matters that were awaiting our attention.

“But surely, sir, we ought to turn over every conceivable stone in endeavoring to retrieve the lost volume,” I plaintively replied in response to his directive to desist.

“My friend, there are many more stones on this earth than you or the police can ever hope to overturn, and if our thief desires that the book not be found, then it is most likely it will not be. One must, after all, assume that the miscreant is intelligent enough to wait some considerable time until things have cooled a bit, wouldn’t you think? Surely he will not be such a dolt as to tip his hand even as the police are still searching.”

And with that irrefutable bit of logic placed squarely on the rhetorical table, the matter was ended, at least as regards our efforts to track the thing down. We would leave it in the hands of the authorities who would, in turn, make a final determination for Lloyd’s benefit in the coming weeks, following which they would render to Weaverling a very substantial settlement check indeed.

All of which would seem to have drawn the entire affair to a rather anticlimactic and unsatisfying conclusion, what with no book or thief identified nor the details of the nefarious scheme revealed. But the discerning reader will require none of these, for the facts of the matter admit only one possible resolution. Who among the attendees in Weaverling’s library that night was aware of the existence of the safe or, for that matter, any of its contents? Who, aside from Patterson and Weaverling, knew in advance who the target of that evening’s fictitious assassination would be? And who knew precisely which glass was Weaverling’s favorite from which to sip brandy? The answer must surely be that it was your correspondent, and he alone, who knew all of these things, and that, indeed, it was I who made off with the blood edition.

Having judged, from a long history of drinking with the man, that Weaverling’s pace of imbibing, and thus repeatedly bringing his lips into contact with a suitably administered sedative placed in advance around the glass’s rim, would cause him to pass out well after the departure of his guests from the library, and having scheduled my errand and subsequent reappearance at the house for well after that time, it was then a trivial matter to place the taunting note (penned for me by an unsuspecting business associate days earlier), employ Weaverling’s unconscious thumb to open the safe, abscond with the volume, and close it up again before dutifully contacting the police. Indeed, the priceless edition lies even now safely ensconced in a safe deposit box inside the very bank whose sister corporation wrote the original insurance policy on it. One might say they have, in fact, recovered that for which they will shortly pay so dearly, except that they are, of course, unaware that it rests safely within their very own premises.

In the end, it proved useful to invoke Patterson’s presentation, as well as Hedges’ unexpectedly propitious outburst, to deflect attention from what the police might otherwise have discerned to be my possible connection with the events of that evening. But, in the absence of all but the most circumstantial of evidence, the events were construed to have taken place during my well-witnessed absence from the room, and so they never felt it necessary to undertake any but the most cursory interview with the victim’s loyal and appropriately distraught assistant.

But why, one reasonably asks, would a trusted colleague stoop to such an ignominious undertaking? I offer no apology save that as a lifelong bibliophile, I found the temptation unavoidable. Weaverling’s pecuniary and bibliophilic blessings are, after all, legion, and I justify my theft of the volume as the man’s unwitting bequest to me for my many years of faithful service, a rationalization he may well be comfortable with himself, as he seems to have been all too ready to abandon the search and accept the insurer’s check. Indeed, it’s entirely possible that Weaverling knows precisely what transpired that night and saw in it the opportunity to effect the bequest I imagined while simultaneously realizing a not insubstantial bit of compensation as part of the arrangement. The man, while old and infirm, is no fool, and the glances he has cast my way in recent days, as well as his peremptory cessation of my investigatory efforts, are both suggestive of a mind at peace with itself. At risk of stretching credulity to the breaking point, it’s conceivable he even finds the whole affair somewhat clever on my part. But that may be asking a bit too much.

1 Comment

Very amusing. Nice narrative voice, reminiscent of P.G. Wodehouse crossed with Conan Doyle. Satisfying plot!