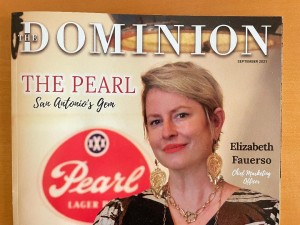

One of my casual comments to Pearl Chief Marketing Officer Elizabeth Fauerso went something like this: “If the Pearl keeps adding high-quality restaurants, shops, and other facilities at the rate that it has in its first twenty years, it’s only a matter of time before out-of-towners start associating San Antonio with not only the Alamo and the Riverwalk, but the Pearl as well.” Upon reflection, it was clear that I underestimated the impact that this twenty-two acre development has had on the city, its residents/visitors, and on local economics, as Elizabeth observed by responding that the Pearl was already very much a part of what visitors associate with the city. Point conceded.

One of my casual comments to Pearl Chief Marketing Officer Elizabeth Fauerso went something like this: “If the Pearl keeps adding high-quality restaurants, shops, and other facilities at the rate that it has in its first twenty years, it’s only a matter of time before out-of-towners start associating San Antonio with not only the Alamo and the Riverwalk, but the Pearl as well.” Upon reflection, it was clear that I underestimated the impact that this twenty-two acre development has had on the city, its residents/visitors, and on local economics, as Elizabeth observed by responding that the Pearl was already very much a part of what visitors associate with the city. Point conceded.

However, in order to fully appreciate the architectural, cultural, and economic contributions the Pearl has made to San Antonio during its brief lifetime, it’s worth stepping back for a moment and considering the history of the area and how it achieved its current status as one of the preeminent urban development projects in the United States. The story starts in 1881 at the Kaiser-Beck Brewery in Bremen, Germany, and an enterprising brewmaster who immigrated to San Antonio in the early 1800’s. Upon commencing operations here in the Alamo City, he observed that a freshly poured glass of the new brew resulted in bubbles that resembled sparkling pearls. From such inspirational moments are enduring brands born, and so it was with what would become Pearl beer. A brewery was promptly opened in San Antonio, known initially as the J. B. Behloradsky Brewery.

Fast forward to 1902 and Otto Koehler had by now taken over the top job at the recently renamed San Antonio Brewing Company and begun brewing Pearl beer at a site just north of downtown along the San Antonio River. Ever ambitious, Koehler in the ensuing fourteen years would grow Pearl beer production to more than 110,000 barrels/year, making the San Antonio Brewing Company the largest brewer in Texas. By this point, the beer had been named “XXX Pearl,” the three X’s an homage to European nomenclature asserting that the symbol was indicative of the highest quality. Otto remained in charge at the Pearl until 1914, on which auspicious date he passed away and control of the brewery passed to his wife Emma.

We need to digress here for a moment and note that the phrase “passed away” is a bit of an understatement in Otto’s case. As it happened, Otto was a bit of a player when he wasn’t busy running the brewery. When his wife Emma was injured in an auto accident, he thoughtfully hired a live-in nurse named Emmi to help out. She, in turn, had another nurse friend—a third Emma—who also agreed to lend a hand, and Otto set both of them up in a small house nearby. In short order, he was conducting affairs with both women while his wife was home recuperating from her injuries. Then came the day in late 1914 when Otto went to the house to pay a visit, only to be shot dead by (the third) Emma, who laconically remarked to police following the incident, “I’m sorry, but I had to kill him.” A few years later she was acquitted of all charges by an all-male jury. Go figure (worth noting, though, that the defendant ended up marrying one of the jurors from her trial).

And so, Emma (the wife) took over the running of the brewery, just in time, as it happened (January, 1920), for Prohibition to come into effect a few years later. Emma was intent on keeping the brewery in business, though, and deftly managed the place through Prohibition’s end in 1933, manufacturing and selling a variety of non-alcoholic products throughout that long period—soft drinks, ‘near beer’ (whatever that is), groceries, ice cream, etc. She even did dry-cleaning and auto repair in order to avoid having to lay off any brewery employees. In the end, Emma proved to be a gifted businessperson, so much so that when Prohibition ended at 12:00 a.m. on September 15, 1933, she was ready to ship product, and had trucks and rail cars filled with beer rolling out just minutes after midnight.

By 1943, Emma was ready to step down from running the brewery and chose nephew Otto Jr. to take over the reins. Stepping on the gas here a bit (else this could easily turn into a book), suffice it to say that much drama ensued throughout the remainder of the forties and fifties (including changing the name of the brewery in 1952 to The Pearl Brewery), with the production of Pearl beer unabated throughout this period. By 1969, though, growth had become a serious challenge (this was, by now, the era of Anheuser Busch, Miller, etc.), and the Pearl brewery was acquired by a conglomerate, which, following another series of complex mergers and acquisitions, ended up combining the brewery with other properties under the Pabst brand. By this point, the writing was on the wall, and in 2001, the employees, after making Pearl beer along the San Antonio River for something like 118 years, departed the factory for the final time.

All of which left behind an industrialized property covering some twenty-two acres and no obvious plans for what to do with it. Enter, a year later, Christopher “Kit” Goldsbury and Silver Ventures, who purchased the property outright and promptly began an ambitious development plan that would ultimately revitalize the area into the urban enclave that San Antonians (and visitors from near and far) know and love today.

“When the property was first acquired,” relates Elizabeth, “it was one hundred percent ground cover, i.e., asphalt and concrete, without a tree to be seen. And the river was completed inaccessible.” Elizabeth is a native San Antonian, and so it was perhaps fate that drew her back to the site where many a father and grandfather worked back in the days when the brewery employed something like eighteen percent of the entire city workforce. In fact, her family on her mother’s side goes back eight generations and hails from the original Canary Islanders who first came to this area back in 1731. She had moved away and was working in Dallas when the call came asking if she might be interested in working to help continue the development and marketing of the Pearl. By that time in 2011, work on the development was already well along, Johnny Hernandez was preparing to open La Gloria, and the Culinary Institute of America was just gearing up to open its third campus on the site.

Elizabeth speaks with passion about the three pillars that have underpinned the vision for developing the Pearl site, pillars that apply as much today as they did when work began two decades ago. The first is preservation of the brewery’s history.

“Silver Ventures’ vision was always to preserve as much of the history of the brewery as possible,” she says. “If they hadn’t come along when they did, it’s nearly certain that all of this would have been torn down.” These preservation efforts are apparent every place you go in the Pearl complex, but perhaps no site more so than the Hotel Emma, the flagship structure (and original brew house) named for the founder’s wife. The original developers of the brewery back in the late nineteenth century engaged brewery designer August Maritzen of Chicago, who, in turn, hired German masons who used the limestone and brick that were prevalent in the area. “The fact that these structures were still here 100 years later, though they needed some love and care to bring them back, makes them important buildings to the history of San Antonio,” says preservation architect Jeffrey Fetzer. “These buildings have had a long, important history in San Antonio and Silver Ventures was committed to preserving that.”

“The craftsmanship of the industrial objects left behind was so high,” Elizabeth adds. “The chandelier in the Hotel Emma bar was once the top of a bottle labeler. There are just so many materials that are super high quality. The architects kept three tanks in the bar for seating, a room that once held thirty of them. And there was so much additional old stuff that has been saved for possible use in future building projects.”

The second pillar that would come to define the Pearl was the culinary arts and a passionate appreciation for the role that food plays in the community. Thus, attracting the CIA to open just its third U.S. campus here in 2011 was key to realizing that vision. “The school is the center of the wheel,” Elizabeth says, “and of our commitment to offering unique culinary experiences. You will see spaces here for chefs, makers, anyone who’s committed to culinary creativity. We were advised when we first started development that the maximum number of chef-driven restaurants that an area of this size could support was four. We now have twenty-three with more on the way. After all, getting together around a table for a meal is one of our core cultural activities. We’ve also run a weekend farmer’s market here since our inception, one with a 150-mile radius from which all of the products must come. When we say ‘local,’ we mean it.”

The third pillar upon which the Pearl’s vision rests is the notion of the urban plaza. “It’s a gathering place,” Elizabeth says, “one that offers a diversity of experiences that are available at all times and are representative of the city. Before designs were completed for the Pearl, much research was conducted in other plaza-rich locations like Mexico City, Granville Island Vancouver, etc. But at the end of the day, we wanted it to be a co-creation with the San Antonio community.” And because the Pearl is both in and of the San Antonio community, it contributes in ways that transcend the cultural and culinary. It is a significant draw for out-of-towners, whether for conferences or tourism, with all of the economic benefits that come along with that. The development has also had significant knock-on effects in the surrounding neighborhood, as demonstrated by the nearly completed Credit Human complex and other businesses that have sprung up along the south Broadway corridor.

“In addition to the original three-pillar vision for the Pearl, our ability to contribute to the creation of a growing, vibrant surrounding neighborhood is of critical importance,” she says. “These are the ways I always orient toward a city—most accessible and most intimate, i.e., ways to understand a city through its food and its public spaces. The Pearl never closes; we hold ourselves to a neighborhood standard, and a neighborhood doesn’t close. And yes, the top three things people talk about in San Antonio now include the Riverwalk, the Alamo, and the Pearl. What we’re learning as a city is that the more people travel, the more they want these unique cultural experiences. As our understanding of these desires evolves, we’re doing a better job of putting forward the story about unique experiences, foods, and spaces.

The Pearl’s very first tenant opened for business in 2006, The Aveda Institute, purveyor of environmentally friendly personal products, built on the site of the brewery’s original garage. Soon thereafter (2009) came projects driven by Chef Andrew Weissman, Il Sogno and the Sandbar Fish House and Market. That same year, the weekend farmer’s market began in earnest, featuring everything from farm-fresh produce and dairy to honey, salsa, and gourmet candies. 2011 saw the opening of the amphitheater as well as La Gloria and the CIA campus, along with its student restaurant Nao (recently replaced by Savor). And, finally, in 2015, following an epic renovation of the original brew house, the Hotel Emma, and its marquis culinary properties Southerleigh and Supper, was opened along with the Sternewirth—Hotel Emma’s Bar and Clubroom—and the Larder. Finally, in 2019, the Food Hall opened in the former bottling department building, offering six eclectic casual restaurants and a large courtyard with splash pad, all sitting atop the underground JazzTX club, run by pianist and entrepreneur Doc Watkins.

The Pearl works closely with numerous city nonprofits to create memorable events and experiences. These include, for example, Dios de los Muertos celebrations, monarch butterfly festivals (San Antonio is a pathway city through which monarchs pass on their annual pilgrimage to/from Michoacán, and during the festival schoolchildren are given their own chrysalises to grow butterflies.), and Chanukah events in coordination with Rabbi Teldon that feature kosher food prepared by CIA students.

In addition to contributing to San Antonio in cultural, culinary, and economic ways, the area also serves as an icon for what is achievable on the sustainability front. When the Pearl developers re-opened the Full Goods building, it was the largest solar installation in the state of Texas. “We have significant rainwater recapture capabilities,” Elizabeth adds, “as well as a purple piping system that recycles all HVAC water. We have property-wide recycling, and we also worked closely with CEO Steve Hennigan at Credit Human to create one of the most sustainable LEED Platinum certified buildings in the country, a facility that is ninety percent more efficient than comparable sized buildings elsewhere.

What’s next for The Pearl? Elizabeth was a bit coy on this one, but assured me that plenty more plans are in the works—both cultural and culinary—some of which they expect to announce in the coming few months. “For sure there will be more food, more engagement, and more creativity. Also, the Pearl owns more land on the other side of the river, so we have plenty of room to grow.”

So, yes, the Pearl is about providing economic opportunity for the city. But more importantly it’s about connecting San Antonio to its traditions and its history. “A lot of the traditions that we celebrate here,” Elizabeth says, “are about the people who have been at this for generations—brewing, cooking, making. But there is also an entire world of really creative new people who want to come here and innovate and be makers for the modern generation. On some level it’s about realizing and embracing the fact that what’s old can be new again. To be a part of creating a special place where that can happen is a wonderful thing.”