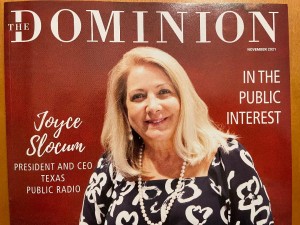

I first met Texas Public Radio (TPR) President and CEO Joyce Slocum in 2016, when she was a speaker at the TEDxSanAntonio annual conference. She was the final speaker of the daylong event, and quipped that the slot was a challenging one, as she was the only thing standing between the 800-plus audience members and “adult beverages.” With this admission, Joyce proceeded to spell out the philosophy that has allowed her to be successful in her professional and personal life, a philosophy she summed up with the two simple words “be nice.” In the brief but compelling remarks that followed, she provided numerous examples of how her life had taken unexpected but advantageous turns through a combination of personal civility and seizing on the opportunities that presented themselves.

I first met Texas Public Radio (TPR) President and CEO Joyce Slocum in 2016, when she was a speaker at the TEDxSanAntonio annual conference. She was the final speaker of the daylong event, and quipped that the slot was a challenging one, as she was the only thing standing between the 800-plus audience members and “adult beverages.” With this admission, Joyce proceeded to spell out the philosophy that has allowed her to be successful in her professional and personal life, a philosophy she summed up with the two simple words “be nice.” In the brief but compelling remarks that followed, she provided numerous examples of how her life had taken unexpected but advantageous turns through a combination of personal civility and seizing on the opportunities that presented themselves.

Born and raised in Dallas, Joyce has two older brothers, one an attorney, the other a trained physicist, now retired from his role as supply chain manager for the chemical industry. Her parents divorced when she was quite young, and Joyce and her brothers were raised largely by their mother, though with plenty of assistance from maternal grandparents who lived in Victoria, as well as various aunts and uncles in the area. She describes Texas as a familiar and comfortable place to be from, and one she has happily returned to more than once (more on that shortly).

Joyce was never much into high school, so much so that she opted to leave after her sophomore year at age sixteen. Searching for alternative means of education that would be more effective and rewarding, she ended up speaking with a family friend who happened to be president of a small Illinois community college called Joliet Junior College. Believing that a change of scenery might be just the ticket to a better education, and overcoming the reluctance of her mother to her sixteen-year-old daughter moving away and being surrounded by college aged kids, Joyce enrolled at Joliet under a somewhat unorthodox arrangement, seeing as how the college had intended its early admissions program to appeal primarily to high school dropouts who were interested in vocational training. She was admitted on a provisional arrangement in which she was required to maintain a B average for three semesters, following which her status would then be upgraded to that of full-time student.

“I was definitely a girly girl growing up,” Joyce recalls. “I was into ballet, cheer, and drill team. My brothers were more intellectual, but I never considered myself to be that way, at least not until I got to college. When I was very young, I didn’t even anticipate having an actual career. I imagined I’d become a wife and a mother. After the divorce, I saw all of our neighbors kind of feeling sorry for my mom because now she had to work to support us. And no, my family and friends were most definitely not supportive of the idea of me leaving high school so early. But in the end my mom was very encouraging. She insisted that I take actual academic courses though, not just a bunch of basket weaving and ceramics classes. I guess in a way I was following in my brothers’ footsteps, since they also both left high school early to go to college.”

In the end, she successfully completed the program at Joliet and transitioned from there to Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville, where she obtained her undergraduate degree in sociology and political science. Her vision throughout these years was that she would follow up her undergraduate studies with a stint in law school, ideally back home in the Lone Star state at UT Austin. But, as events transpired, her undergrad advisor was a graduate of the law school at St. Louis University, and he encouraged her to apply there. She later traveled to St. Louis for her admission interview, and, while waiting her turn, struck up a conversation with a woman who was also waiting there for a moment with the dean of the school. Later, upon receiving notice that she had been accepted to the school, she also received the good news that she had been awarded a full scholarship—good news and also totally unexpected since she had never even applied for the scholarship. Turned out the woman she had spoken with at the dean’s office had been someone intent on working with the dean to create a new family scholarship endowment, and she had quickly identified Joyce as a perfect inaugural candidate to receive it. In the end, accepting the scholarship was a less expensive option than returning home and attending UT.

Thinking back on her law school days, Joyce remembers discovering that for the first time she had to actually apply herself and study hard to make it through.

“I was smart enough to have had a relatively easy time of it in high school and at Joliet and Southern Illinois. But when I got to law school, it turned out everyone else was smart too. I pretty quickly got together with a good friend and we created our own study group of two. We were so totally connected that we ended up completing each other’s sentences.”

Joyce’s plan had always been to return to Texas after graduating from law school. And so, one day while flying to Dallas for the usual end-of-second-year round of law firm interviews, she happened to sit next to an ordinary-looking gentleman in jeans and boots. “We struck up a conversation,” Joyce says, “and he told me he was an attorney as well. He asked why I’d gone to St. Louis for law school rather than one of the better known schools, and I told him they’d given me a great scholarship and a great education. When we reached Dallas and were getting off the plane, the man asked for a copy of my resume. Well, turned out he was on the recruiting committee for a Dallas law firm called Johnson and Swanson, one of the most prestigious in the city at that time. Years later, after I’d been working there for a while, the fellow admitted that he’d recommended hiring me because the firm ‘desperately needed someone who didn’t have their nose in the air.’”

Joyce did eventually begin searching for a new opportunity, having grown somewhat bored with tax law, which she describes as ‘spending countless hours in the library reading tax codes.’ Through a friend, she got a lead on an opportunity at The Southland Corporation, the firm that owned the 7/11 chain of convenience stores. She would subsequently go on to spend almost ten years there doing international licensing and franchise work. She deeply enjoyed the work and her colleagues, and it allowed her to remain in her home town of Dallas. However, the job entailed frequent travel, which, in turn, meant lots of time in cars traveling to and from the airport. And it was in one of these cars that her life would change once again, this time a bit more dramatically.

“My favorite driver was a guy named David Davodi, and we would engage in long conversations each time I traveled with him. Turned out he was a frequent driver for a woman named Sheryl Leach as well, also from Dallas and an executive with Lyrick Studios, and the creator of the wildly popular Barney TV character. Davodi repeatedly exhorted me to take a meeting with Leach, and he had also, as it happened, been spending a fair amount of energy talking up my background with Sheryl. Long story short—we finally met over coffee, and what was supposed to be a half-hour meeting turned into three hours. She offered me a job as in-house counsel for the company, and that’s how I became Barney’s lawyer!”

Any hesitancy Joyce had about leaving a large established law department and creating a new one from scratch was quickly overcome and Joyce took to her new role with the same verve she had applied to her other positions. In the end, she would spend fourteen years with the company, handling everything from the legal aspects of having a Barney balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade to creating agreements for child television actors and their parents. Eventually Lyrick was merged with HIT Entertainment and that meant Joyce’s portfolio of responsibilities grew to include not only Barney, but other beloved childhood properties like Thomas the Tank Engine and Bob the Builder.

In 2008, as Joyce began giving serious thought to her next career move (HIT had been acquired by a private equity company that was planning to close the Dallas office), she was approached by a colleague from PBS who had become aware that the general counsel for National Public Radio (NPR) was planning to retire soon. And so, although she wasn’t terribly keen on moving from Dallas to Washington D.C., she took the plunge and applied for the position.

“It was actually quite a process getting in the front door at NPR. The first woman I interviewed with quit the company two days later. Immediately after that, my scheduled interview with then-CEO Ken Stern was cancelled because he had just been fired. When I expressed a bit of concern about the way things were going, a couple of NPR board members got me on a video conference and assured me that they had a vision for the role and they very much wanted me to take on the challenge. When I got there I discovered that the department was still operating very much in the dark ages. It felt like they were chiseling legal documents onto stone tablets.”

What was intended as a two-year stint to modernize the NPR legal department turned into five and a half years with the organization. Joyce arrived at the start of the 2008 recession with its associated steep drops in philanthropic contributions, which meant that her unfortunate first challenge would be organizing the laying off of a significant number of staff. In addition, union/management relations at that time were so fraught that there were over two hundred outstanding grievances awaiting the new lead counsel’s attention. While serving as head lawyer for the organization, Joyce also served as Chief Ethics Officer. She found herself in the midst of the Juan Williams imbroglio as well as various other controversies. After conservative activist James O’Keefe III released a video of NPR development staff meeting with representatives of the purported Muslim Education Action Committee—later determined to be heavily edited to distort the actual conversation—then-CEO Vivian Schiller tendered her resignation, opening up the CEO position, for which Joyce was asked to serve in an interim capacity.

“It wasn’t a role I particularly wanted at that time, but most of the rest of the executive team members were quite new. I had worked with pretty much every other department within the organization and so I agreed.”

It was while serving as NPR’s interim CEO that Joyce became instrumental in creating one of their now flagship programs, the TED Radio Hour, which came about from a series of conversations she had with TED executives, one of whom she had become acquainted with during her days at Lyrick/HIT.

She would serve in that interim role for nine months before NPR finally hired Gary Knell as the new permanent CEO. In response to the obvious question about why Joyce wouldn’t have made an excellent candidate to take the role full time, she clarifies that the board had, as part of its succession planning, included a provision stating that interim candidates were not eligible to be considered for the full-time role. However, in an ironic (and perhaps inevitable) twist, she did end up being strongly encouraged to apply for the permanent CEO position when Knell left a short time later. But in the meantime, Joyce took on the new role of Chief Administrative Officer, a position that included responsibility for organizing the construction of a new headquarters building for NPR. This responsibility would last an additional couple of years and would turn out to be excellent experience for when she made her way back home and took over the reins at Texas Public Radio.

By 2013, Joyce had had enough of the Washington DC weather, traffic and politics and was looking for a new opportunity that would get her back to Texas. In a fortuitous confluence of events, the prior CEO of TPR had recently left and the role was being temporarily filled by a team of TPR’s existing executives. In the end, there were a few fits and starts and postponements getting unwound from her NPR responsibilities.

“The TPR board was very understanding about my desire to leave things at NPR in good order, but they understandably wanted their new CEO in place. I finally set a firm date to leave NPR in December of 2013,” she recalls. “My last official act at NPR was serving as the executive sponsor for the office holiday party!””

When Joyce arrived in the Alamo City, TPR was still working out of their original building on Datapoint Drive near the medical center. But relocation to someplace newer and better was already being talked about.

“We wanted a location that was much more centralized, one that would provide better access to the community and to our staff members. After much searching up and down the Broadway corridor and other places across San Antonio, Judge Wolff suggested that we consider building out the brand new (but still empty) building abutting the Alameda Theater. It had originally been constructed as part of a larger project intended to revive the theater, and was intended to be a back-of-house facility for constructing sets, handling wardrobe, and things like that. In the end, that revival of the theater never happened, which left the building available.”

Joyce now sits on the board of the Alameda Theater Conservancy (among numerous other community roles) and she envisions a time in the near future when the theater and the station will be very collaborative. With funding for the theater revival now back on track with money from the city and the county, the prospects look more optimistic than ever.

The new TPR headquarters building, located at 321 West Commerce, adjacent San Pedro Creek, provides a wealth of facilities that include a small theater and a variety of conference facilities for community gatherings, or at least that was the plan before Covid.

“We had a big calendar of programs on tap when we first moved in, but of course we had to pivot like everyone else when the pandemic struck. We definitely want people in this space though, just as soon as it is practical to do so. We’re also excited to see the completion of construction projects along San Pedro Creek, including St. James Plaza. It will celebrate the St. James AME Church that used to be there and be used as a performance space. Our bigger vision is for this part of town to be a walk-able cultural hub, with the Tobin, Aztec Theater, and other facilities nearby.

“What I really love about our new location is that we’re creating a place of unity at a spot that was historically considered a dividing line in San Antonio. West of San Pedro Creek was thought of as Hispanic, east as Anglo. We want to be an organization that helps to bridge those sorts of gaps. We have a series called Dare to Listen that’s designed to get people together who have widely disparate views on social issues, and to then talk honestly about those issues. But we’re careful every day to not take a political stand on things. Our job is to give people context and share facts and then let them make up their minds, to provide an opportunity for civil discourse.”

Another big challenge for Joyce and her colleagues at TPR is creating a more cohesive platform for all of the stations that comprise the TPR family. It isn’t just about San Antonio. TPR operates stations in the Hill Country, Llano/Marble Falls, Del Rio, Midland/Odessa, and Gonzales. But those stations do not have their own dedicated news teams or other resources, relying instead on content coming out of San Antonio.

“They are not,” she says, “providing truly local coverage, although making that happen is part of our long-term vision. We also need to figure out how to get better coverage in the Rio Grande Valley, which happens to be the largest metropolitan area in the U.S. without its own public radio service.”

Joyce has also led the creation of several new podcast projects, including one called Demented, which is about becoming a caregiver for one’s parents. It’s being sponsored by UT Health, which is an excellent fit because they have the Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases that has just received an important NIH Center of Excellence designation. They’re also launching a podcast program entitled Out of Uniform about veteran’s issues and the challenges of reintegrating into the community following military service. Finally, a program called Cross Country is being developed to help create a broader understanding of the far-reaching impact of issues happening at the border.

In summarizing her long career, Joyce comes back repeatedly to her original mantra about being nice to one’s colleagues and contacts, and she attributes all of her opportunities and successes to instances in which she had collegial conversations, whether with adjacent passengers on a flight, a limo driver, or someone in the seat next to her in a waiting room.

“When all is said and done, I am about building community. That’s so important; it’s how we overcome all the polarization we’re feeling today, this seeming inability to come together. I want to draw people together and make them feel like they’re part of the same opportunity—to help highlight our shared values and goals.”