Introduction

Introduction

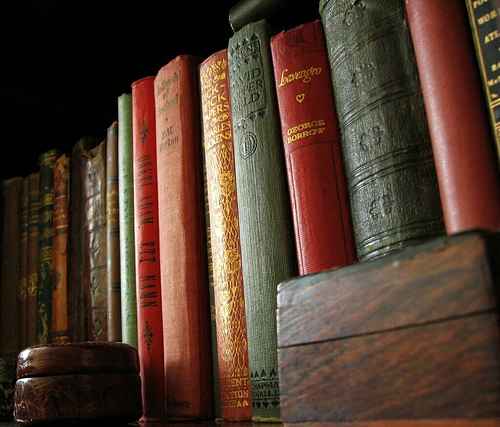

For as long as I can remember I have had a problem with books. As a general matter, I love them, and, as a consequence, cannot bear to part with one once I have it. This state of affairs has been true pretty much since college, and to prove it I still have every book I ever bought back in those heady days, including many engineering books now so hopelessly outdated[1] they may as well be about how to manufacture rope from indigenous grasses. Doesn’t matter though; I still have them on my shelves and that’s the important thing. But my inability to discard books is not, strictly speaking, the topic of this essay. I mention it only to provide context for the somewhat dense and recondite material to follow. The task I have set myself with this bit of exposition is to explain the many and various nuances of rare-book collecting, at least as I’ve come to understand them from my several years at this avocation.

Book collecting is the sort of pursuit that can lead to madness[2], and it is very important for the neophyte to fully understand the magnitude of what he is getting into before stepping toward the precipice. This is, of course, true in dealing with any collectibles, but the nuances associated with book collecting are truly beyond arcane, and making mistakes of judgment can turn out to be frustrating and more than a little expensive. I should add, by way of further clarification, that I will talk here specifically about collecting what are known in the book trade as First Editions, and even more specifically, First Editions in modern American fiction[3]. It’s worth limiting the focus in this manner right from the get-go, because as nuanced as this sort of collecting turns out to be, there are plenty of additional details that attend collecting, say, antique Bibles or original copies of Audubon bird painting books, that can only serve to exacerbate an already fraught topic.

So there we are: American fiction First Editions. But where to begin. The term First Edition itself is as good place as any[4]. The phrase is so rife with ambiguity and misunderstanding that many well-meaning collectors never make it past this initial rite of passage. They are enamored with the concept though, and confidently walk into their nearest used book store asking for a “First Edition” of, to pick a random example, Harper Lee’s classic (and only) novel, To Kill a Mockingbird. “It will make a nice birthday present for my grandfather,” they say. “Sure,” the intrepid book purveyor replies. “Just got a copy in this very morning and it’s only twenty dollars.” Our uninformed and unsuspecting customer walks out of the store thrilled at having made the steal of the century, utterly unaware that his copy of Lee’s classic is worth not a penny more than what he paid for it, and, in all likelihood, a good deal less, by any objective measure, seeing as how the book purveyor’s job is, after all, to make a profit from what he sells in his store[5].

There are, in fact, many things that our neophyte book buyer does not know about his purchase. And in truth it may not matter a whit if all he is after is a nice readable copy of the novel. If, however, he hands it to grandpa on the pretence that it is a true First Edition, and if, heaven forbid, grandpa knows a thing or two about books, our buyer is likely to learn a hard lesson before the exchange is over. By way of introducing some of the opinions and insights soon to follow, let me here list a few of the possible editions our book buyer may, in fact, have walked out of the store with, setting aside until later the matter of the twenty dollars, and whether it was money wisely-spent. Our well-meaning book buyer may have purchased:

1. A true First Edition, First Printing of To Kill a Mockingbird

2. A First Edition, but later printing of the book

3. A First Edition, later “state” of the book

4. A First Edition, pre-publication printing

5. A First Edition, Book Club Edition of the book

6. A faux/facsimile First Edition, such as those published by the First Edition Library

7. A First Edition in paperback

8. A specially-bound edition, such as those produced by the Franklin Mint or Easton Press

All of which raises the obvious question “Then what in the hell does it mean to search for and buy a First Edition of a novel?” In truth, this is a question only each individual can answer for himself, for it boils down, ultimately, to what you want to be a collector of. I will, at this point, further clarify my own situation by stating that I am obsessively focused on finding and collecting First Edition/First Printings. It is critical that you think through and answer this question for yourself at the outset, because different answers will cause you to search/shop for very different things, and to come at the exercise with very different pecuniary expectations. Much more detail will follow, but suffice it to say for the moment that our example shopper could, for his twenty dollars, have reasonably come away with only the fifth, sixth, or (possibly) eighth choices presented above, for reasons that will shortly become apparent.

First Printings

The First Printing of a novel is typically the quarry of choice for the serious book collector. It is the first release of a novel by the book’s original publisher, and it is almost always (but not necessarily) a hard-cover edition, very frequently including a paper dust jacket (though, again, not always). Depending on the book’s success in the marketplace, it may have gone on to subsequent printings and may have been released, as well, in a paperback and/or Book Club Edition. If it really did smashingly in sales, or was later deemed an important/classic work, it may have also been subsequently published in an entirely different edition[6] by a completely different publisher, just to confound things further. It would be inaccurate to assert, as a blanket statement, that First Printings are always the rarest editions, though this is the case more often than not. This is so for many reasons, not least of which is that writers, as with any other vocation, tend to start their careers as relative unknowns, meaning that the publisher will typically have hedged its bet by only releasing a small initial print run (the First Printing) to see how it sold before launching into later editions. This is why the early works of now-well-known authors, e.g., Cormac McCarthy and Thomas Pynchon, are so rare and expensive[7].

So how, then, do you discern whether that twenty-dollar copy you walked out of the store with is, in fact, a First Printing or one of the more mundane alternatives? The first step with any such purchase should be a good bit of on-line research. With relatively brief visits to web sites like www.abe.com[8] or eBay[9], supplemented by detailed conversations with your favorite book purveyor, you can readily obtain all of the salient information about a particular edition, including issue points (more on these in a bit), typical conditions for the title, and a range of prices you should expect to encounter. As with any significant purchase, the more facts you gather before walking into the shop, the better condition you’ll be in to make an informed decision.

The Copyright Page

Any assessment of a First Edition’s value and provenance begins with a look at the copyright page. This is the (almost always left-facing) page immediately following the title page, on which is displayed the publisher’s name, publishing date, and other assorted details. There are numerous items that may appear on this page, each of which is described below. The bad news is that there have never been much in the way of standards about how this information is to be presented, nor which, indeed, is even provided. For nearly every statement made in the following paragraphs, there will be exceptions. About the only general statement one can make about a copyright page is that pretty much every book published has one, and it’s nearly always on the left side. Beyond that, the devil, as ever, is in the details.

- Publisher name and year – There will appear near the top of the page the name of the original publisher of the novel and the year of its release. Publishing houses include Random House, Viking, Scribners, and countless others. Every publisher has its own way of presenting copyright information, besides which, for good measure, they periodically change how they do it even within a publishing house, either because of having been bought by another publisher, or just out of sheer cussedness.

- The phrase “First Edition.” An important rule to remember – every First Printing is a First Edition, but the converse is by no means true. The phrase First Edition appearing on the copyright page can mean various things, but typically it indicates that the edition in your hands is formatted the same as the First Printing, i.e., same text block size, fonts, book layout, etc. But, even a book whose copyright page says First Edition can exhibit numerous subtle differences between it and the true First Printing. Examples include:

-

- Typos from earlier editions may have been corrected in later editions[10].

- The price can be different. As newer editions get released, prices, of course, will tend to rise, and this is often reflected on the dust jacket.

- The contents of the dust jacket can change. While the text block should be the same (except for repaired typos), there are frequently changes, sometimes very subtle ones, between the dust jackets of first and later printings[11].

- The phrase “First Printing” – Once in a while you will get lucky and a publisher will actually include the phrase “First Printing,” big as life, right there on the copyright page, in which case, nine times out of ten, you’re home free. It’s that tenth time that’s the killer, though, because once in a while that phrase, despite all appearances to the contrary, will NOT, in fact, indicate (necessarily) the true First Printing that the purist is seeking. A notable example of this is the true-crime novel In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, numerous later printings of which are floating around with “First Printing” boldly displayed on the copyright page. Sometimes, just to be really obnoxious, Book Club Editions will also cavalierly use the phrase in their (typically much later) print runs.

- Number Line – Many publishers include what is known as a number line near the bottom of the copyright page. This will be a single short row of digits that looks something like:

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

or perhaps:

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

or various combinations thereof.

Conventional wisdom (and some uninformed individuals) will tell you with great authority that if you see a “1” in this number line, then the book is, indeed, a First Edition. There is some truth to this statement, but it is incomplete and dangerous if left unscrutinized. As I mentioned earlier, different publishers have adopted their own standards for just what to do with this line. A few possibilities include:

- Ignore it completely – Plenty of books have no number line at all.

- Use it in the expected manner, i.e., provide a full (1 through 10) number line to indicate a First Printing, and remove one digit for each subsequent printing (typically the lowest number you see in the line indicates the printing).

- Place the digits in order, but backwards, as in the first example above.

- Place the digits in some apparently arbitrary order, as with the second example.

- Mess with it in subtle ways for no apparent reason. Random House has for many years, employed the standard that First Printings have a number line that stops at “2.”

The best advice regarding number lines goes back to the initial research statement made earlier. Check several sources and see what they say is indicative of a true First Printing.

- Colophon – A colophon (or Printer’s Mark) is a symbol of some sort, unique to a specific publisher. They are not terribly common these days, but are often important indicators of First Printings from a few decades ago. The Scribner’s colophon looks like:

[1] I still have a copy of a book on programming the Z-80, an 8-bit microprocessor that was a first-generation integrated circuit and pretty advanced stuff…during the Apollo program.

[2] Both for the collector and anyone they happen to live with.

[3] Defined here as Twentieth-Century and upward. Once you start poking around in nineteenth-century books, you’re dealing with cracked morocco leather, foxed paper, and other assorted minutia of the seriously antiquated. I choose also to limit the discussion to American fiction, because non-American publishers violate a good many of the rules discussed herein and sorting that all out would cause this essay to easily double in length.

[4] The term typically connotes the first time the work ever appeared in print. This, in itself, can greatly confuse things, as some books, for example, appear in other countries before they are released in the U.S. Even the very notion of a First Edition being a book can lead to problems. Some works that ultimately end up printed as complete books are first published in parts in magazines like The New Yorker. Hemingway’s classic The Old Man and the Sea appeared in its entirety as an article in LIFE magazine several weeks before the first Scribner’s edition was released.

[5] Don’t even get me started on capitalism and the notion of whether what you pay for something is actually what it’s worth. That will take us way off topic.

[6] Good example, Modern Library editions released in the 50s and 60s by Random House.

[7] Thomas Pynchon’s dense but classic novel Gravity’s Rainbow was originally issued as a 4,000-copy First Printing, examples of which now routinely fetch north of $1,000. Similarly, Cormac McCarthy’s magnum opus Blood Meridian was first issued by Random House in a 5,000-copy run, and good-condition examples now go for in excess of $2,500.

[8] ABE is a web site that aggregates used sales for book shops, large and small, around the world. However obscure the title you’re seeking, if there’s one for sale anywhere, odds are it will be listed on ABE.

[9] A terrific number and variety of First Editions are bought and sold on eBay. Interestingly, whereas ABE is the definitive source for the greatest variety of copies of a given title, eBay routinely has better documentation of items than ABE, the latter of which will typically include a single-paragraph description of the book along with a single photograph. Obtaining more detail usually requires direct communication with the book store in question. eBay sellers, particularly for the priciest items, routinely include numerous photos and much greater detail of description than ABE. Of course, as with any online purchase, caveat emptor applies.

[10] Though, oddly, this is not always the case. You would think that after enough people had scrutinized a book, all of its errors would have been discovered and fixed. Sometimes, though, books go through many printings while retaining their original errors. It is, thus, somewhat humorous when marginally informed book sellers call out a particular error as being a supposed issue point of the First Printing, when in fact the error pervades nearly every edition of the book. A wonderful example of this phenomenon is the so-called “bite for bight” error (pg. 281) that is constantly cited as an issue point in First Printings of John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden. In truth, I have never seen any edition of this book, including the most modern, that did not include this “error”.

[11] These changes can be positively minute, but can, nonetheless, seriously affect availability and valuation. The award for most subtle change from a First Printing dust jacket to a subsequent edition goes to David Foster Wallace’s vast and wonderful novel, Infinite Jest. The First Printing includes eight short review quotes on the rear of the jacket, the final one of which is by fellow writer William T. Vollman. Trouble is, Vollmann actually spells his name with two n’s at the end, an error that was fixed on all subsequent editions, and which is much sought after by would-be owners of the true First Printing.

[12] Printed Oct. 22, 1926, in a print run of 5090 copies.

[13] Author photos often play a role in identifying First Printings, also notably the case in the earlier example of To Kill a Mockingbird, First Printings of which have Harper Lee’s photo on the back of the jacket, whereas subsequent editions do not.

[14] Book collector trick – It is, in fact, possible to largely undo this effect by holding the volume open, starting from the back, and “reading” it, one page at a time, in the reverse direction, i.e., turning each page and running your finger down the inside center of the spine before proceeding to the next page. It takes a bit of time, but the result is usually quite good.

[15] Like, say, The Fountainhead or Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand.

[16] Another book collector tip – Depending on the depth of penetration of the ink from the remainder mark, it is sometimes possible to remove it through the expedient of sandpaper. This takes a good bit of skill, and the value of undertaking the exercise is a function of the book’s value.

[17] A library edition can be as inexpensive as 10% of the cost of a similar non-library edition.

[18] Ink stamps (e.g., “Farmington Public Library”) are commonly found on the title page, the copyright page, either the front or rear inner boards, and, most obnoxiously, on any or all of the three edges of the text block.

[19] First released in an edition of 1,000 copies (divided into several sub-tranches, some signed, some on special paper, etc.) by Shakespeare & Company Publishing in 1922. This is arguably the single most sought-after First Edition in the English language, with the highest-priced current copy of the First Printing, in its original paper wraps, listed on ABE for $389,000. The fact that this book was banned in America for several years only adds to its mystique, scarcity, and desirability, as many of the original copies were confiscated and destroyed in the early going. This fact also accounts for why some of the extant copies are in unoriginal covers, i.e., one clever way of sneaking copies past the censorship authorities was to change the exterior.

[20] The First Printing of The Shining by Stephen King has the code (in tiny font) R49 in the gutter on page 447.

[21] Board is the term used to indicate the front and back covers of a hardback book. While the term suggests wood, it is, in fact, a stiff cardboard, typically covered in a tightly-woven fabric.

[22] The price of nearly any hard cover book appears on the inner front flap, in the upper right-hand corner. Of course, as with nearly all the rules discussed in this essay, there are occasional exceptions here as well.

[23] A particularly notable offender in this regard is William Faulkner’s novel The Unvanquished, nearly all extant copies of which have some variation of brown as their principal spine color, despite the fact that they all started out light gray back when the book was first published in 1938. Gravity’s Rainbow, mentioned at various points throughout this discussion, is also particularly susceptible to fading, due to the vivid orange color used on the jacket. It is a rare copy indeed on which the orange of the spine precisely matches that of the front jacket.

[24] Ensuring, of course, that the absence is not due to its having been cut off, as described earlier.

[25] A good example here would be Frank Herbert’s science fiction classic Dune, true First Printings of which command thousands, whereas the BCE can be had in decent condition for $25 – $50.

[26] The Guns of Navarone, Ice Station Zebra, etc.

[27] The same dilemma arises if you elect to pursue First Printings of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Umberto Eco, Carlos Fuentes, or countless other wonderful, but not American, authors.

[28] I was tricked on this issue once when what I thought was a beautiful copy of John Updike’s best-known novel Rabbit, Run turned out to be a pre-printing edition.

[29] The difference between these two terms being simply that an inscription is a brief piece of writing by the author (greeting, dedication, etc.) as opposed to a simple signature.

[30] Kurt Vonnegut used to have a habit of drawing a humorous self-portrait (frequently filling an entire blank page) along with his autograph. Michael Chabon, on the other hand, likes to draw a small symbol next to each signature that is indicative of the particular book he’s signing. These include, for example, a baseball for autographs to Summerland or a simple key for his signatures to Kavalier and Clay.

[31] Sometimes adhering it to a page, sometimes just inserting it loosely.

[32] Particularly one for which a significant percentage of the purchase price is due to the signature. Some author signatures are extremely rare and valuable, like, for example, Thomas Pynchon, whereas others, say Norman Mailer and John Updike, would sign pretty much anything that went more than a few seconds without moving.

[33] I have a First Printing of Jonathan Franzen’s early novel The Twenty Seventh City that he signed to his brother-in-law using simply his full first name as opposed to his later loopy and much quicker reading/signing autograph. Placed side-by-side one could never guess they were written by the same individual.

[34] The value of such certificates is much debated.

[35] Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel Love in the Time of Cholera was released by the publisher with a color printed promotional postcard, which, if found in an edition now, adds nicely to the book’s appeal and value.

[36] In fairness, it should be acknowledged that these changes, while generally beneficial, have also facilitated an increase in the frequency and severity of chicanery, whether in bogus autographs, inaccurately described editions, or other underhandedness. If you’re displeased with your purchase from a book store, any reputable dealer will work hard to make it right. Achieving this after an unsatisfactory online purchase can be unnerving or downright impossible.

2 Comments

I bought my hc copy of Infinite Jest back in 1997, about a year after it came out. The novel is obviously a first edition, second printing because there is the first edition wording on the copyright page but the number line ends with a ’2′ instead of a ’1′. Thing is the dustjacket has the misspelled Vollman and also on page 981 of the novel itself there is the typographical half circle on the bottom right of the page which I got to know from other IJ enthusiasts was printed only on first edition, first printing. What do you make of that because I’m still confuse as to which printing of the first edition I owned.

That’s a bit of a head-scratcher, frankly. Yes, the misspelled Vollman name on the jacket tells me you at least have a first edition first state jacket. I have two copies of the first printing (one signed!) and they both have the jacket, the “1″ on the copyright page, and the quarter-circle thing on pg. 981 (which I totally didn’t know about, so thanks for that one). My best guess on your situation is that more copies than just the first printing have the quarter-circle thing on pg. 981 (need more research there) and you have a first-printing jacket on a second-printing book, as I know for a fact that the Vollman thing is ONLY on first printings, and I know as well that you need the “1″ on the copyright page. Not sure if that’s helpful or not!