“He just fell over dead in mid-sentence, not two feet in front of me. And this on a day that had actually been relatively uneventful to that point, as least as these days go. Couple of inconsequential skirmishes. No casualties at all, in fact, aside from Flanders there spraining his ankle dodging a mortar round. We were all sitting around over by the depot, winding down a bit, but taking the usual precautions, you know—sand bags, trip wires, couple of lads on watch up top. Preston and I were just having a sit off to one side, drinking a bit of that awful coffee he made, him telling me about this boat he bought just before signing on, and how he’s going to go home and fix it up once we’re done sacking the regime. And he’s just getting to the part about how he’s going to muster up his nerve and make a run at some girl he knew from high school, take her out on the boat and what not, when for no reason on God’s earth there comes this hiss—you know the hiss—and the round takes him straight in the left ear.”

“He just fell over dead in mid-sentence, not two feet in front of me. And this on a day that had actually been relatively uneventful to that point, as least as these days go. Couple of inconsequential skirmishes. No casualties at all, in fact, aside from Flanders there spraining his ankle dodging a mortar round. We were all sitting around over by the depot, winding down a bit, but taking the usual precautions, you know—sand bags, trip wires, couple of lads on watch up top. Preston and I were just having a sit off to one side, drinking a bit of that awful coffee he made, him telling me about this boat he bought just before signing on, and how he’s going to go home and fix it up once we’re done sacking the regime. And he’s just getting to the part about how he’s going to muster up his nerve and make a run at some girl he knew from high school, take her out on the boat and what not, when for no reason on God’s earth there comes this hiss—you know the hiss—and the round takes him straight in the left ear.”

“Never felt a thing. Of that I can assure you, brother. But here’s the weird bit. I remember—don’t ask me why—that his last word on this earth was ‘I’ll.’ A bit sad to see life end on such an optimistic note. Never made it to the end of the sentence, so I’ve no idea what it was he was meaning to tell me. Something about either the boat or the girl, I expect. Preston was a good one, a hell of a good one, and he’ll damned well be missed.”

Bates had just come in off patrol and was going over the key points of the trip. It had been a four-man scouting mission, and he and the two others he’d gone out with had taken turns shouldering Preston’s body back with them, which was doubtless no easy task, since they’d been more than a mile from our camp when it had happened. He paused for a long moment, turning his expressionless gaze toward the ceiling, reflecting, I suppose, on what must surely have been a horrific image. And yet he seemed to take the whole thing with more equanimity than most, due, I suppose, to the extreme number of casualties he’d witnessed in his time with the rebels. In fact, I knew that he’d kept careful track of them all during his years in combat. He’d explained his entire scheme to me some days earlier. He carried a written record of every casualty he’d personally witnessed. Not a lot of detail—just time and date, location, brief statement of what happened: gun shot, landmine, that sort of thing. I was a bit taken aback when he confessed that he’d personally witnessed the deaths of fifty-four soldiers along with an additional eighty-three wounded. The rebellion was by now nearly four years old and it seemed he’d been around for the better part of it.

But here’s the thing—he really didn’t need the written record. If pushed, he could recite to you every last name in his book, along with all the other salient details of each case. He didn’t get into the why of it, but I took it to be his personal way of coping. He was simultaneously recognizing each man’s sacrifice by keeping the records, while also shielding himself from the horror of the situation by boiling it all down to a handful of simple statistics. And he knew not only every nuance of each man’s case, he could recite, as well, a wide range of statistics about the data in aggregate. He knew the exact percentage of men who had died from gunshot, mortar round, or landmine. He could quote you the distribution of their ages. Hell, he even knew the breakdown of which areas of the country they’d come from. Seemed like the more he embraced the numbers, the less he had to think about the faces.

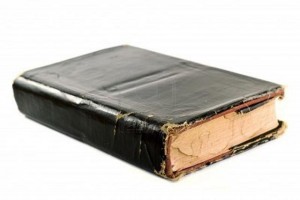

I saw his book of names one time, though it was accidental and I don’t guess he much appreciated it, as he slid the thing quickly back into his breast pocket the moment he spied me looking at him. Previous to him noticing, I had watched fascinated as he scribbled in it with the dregs of a pencil so small he could scarcely hold onto it. The book itself was a miniscule thing, no thicker than your little finger, no taller or wider than a pack of cigarettes. The cover was of an ancient-looking cracked leather material that had once been black but which had evolved with the ages to a sun-bleached gray. It looked for all the world like a tiny bible, truth be told. I did not get much of a glance at the thing before he hid it away, but what little I saw of the two pages he had it open to looked as though he dedicated one full page to each individual’s case. Aside from an almost identical format of information for each man, there was, as well, a curious smudge in the lower right corner of the page. It would turn out that there was one of these on every page as well, though I wouldn’t learn that fact or its significance until sometime later. It also seemed, to my casual gaze, that, as he wrote, he had the book open to a spot nearly at the back of the thing, which caused me to wonder what his plan was if he ran out of pages before we ran out of casualties. I did not think it prudent, though, to ask. That question would be put to the test soon enough.

The regime had not been too terribly particular about the sorts of munitions they dispensed upon us, though they had come to favor in recent days what are known as barrel bombs. These are nothing more sophisticated than spent fifty-five gallon oil drums into which are loaded a great deal of high explosive and the devil’s own share of assorted hardware—nuts, bolts, scrap metal—the better to maim anyone not fortunate enough to be killed outright by the initial detonation. These were dropped in a more or less indiscriminate manner into our midst from cargo aircraft, and designed so as to explode at ground level. I had personally seen only one of these in operation, and that from a safe enough distance to appreciate its efficaciousness while suffering none of the effects myself. The blast itself would generally dispatch anyone within a hundred foot radius, while the flying debris did a fair job of sanitizing things for an additional two hundred feet or so. It is possible, now that I reflect on it, that I have overstated the degree of my own safety in that one instance I witnessed, as I now recall the distinct whistle of a piece of metal flying overhead immediately after the detonation. I was, though, safely ensconced behind a wall and paid it no mind at the time. There are always lethal things flying about these days; we simply do our best to stay out of their way.

We slept fitfully that night, though, I suppose, no more or less so than soldiers have done every night in combat zones since the days of the Greeks. There were the usual two-hour rotations for watch, of which mine occurred around three a.m., just late enough so that it made no sense to try to sleep any further upon its conclusion, what with everyone else rising at around sunup anyway. Aside from Preston’s death, we had seen no direct action throughout the preceding day or night, though we heard occasional deep thumps in the distance as our brethren in various other parts of the city were pummeled. We had no way of knowing the consequences of these distant assaults, though there was every likelihood we would gain some intelligence into this matter before day’s end. Our mission, commencing with the first glint of sunrise, was to rendezvous with another unit, one that had taken heavy casualties, particularly among their leadership, in recent days, to the point where it had been determined that it would be in everyone’s interest for our two units to merge if we could manage it. They had several injured, rendering them relatively immobile, which meant we would endeavor to get to them. Though we had suffered our share of casualties as well, they had all been fatalities, the only positive aspect of which was the fact that our complement of medical supplies had gone largely unused, whereas the unit we were to meet had nearly exhausted their supplies and were apparently in quite dire straits. The last intelligence we’d received suggested that the other unit was some two miles to the southwest, scarcely a half hour’s march under ideal circumstances, Things were, though, hardly ideal at the moment, and we reckoned that if we could effect the rendezvous by nightfall, we would be doing well.

There were sixteen remaining in what we euphemistically thought of us our unit. A month previous there had been thirty-two, so none of us who remained were terribly keen on the way the math was shaking out. We’d actually lost eighteen men and picked up two stragglers along the way. With the rebellion in its current shape—extremely disjointed and disorganized, that is—no one much concerned themselves any longer with units, command structures, ranks, or any of the other niceties of formal military organization. So long as you weren’t fighting for the regime, we were pleased to have you.

We’d buried Preston best we could the previous night. Much as we hated it, simple logistical reality mitigated against us attempting to carry our casualties with us. We did, though, carefully document where each body—or portions thereof—was buried, on the chance that more favorable future circumstances would allow us to return for a proper delivery of the man’s remains to his family—best we could manage under the circumstances. By five thirty that morning, we had gathered everything up, performed a surveillance of our immediate area, took a compass fix, and commenced making our way in the direction of the other unit.

Things went surprisingly without incident for the first mile and a half or so. It was all dense urban environment and we were able to avail ourselves of copious cover from buildings, rubble piles, and assorted other detritus. These slowed our progress somewhat, but also made the trip a good deal less hazardous. Only then, just before noon, we reached the edge of town and suddenly the cover all but disappeared. Before us lay a large clearing—perhaps two hundred yards across—at the other side of which stood the remains of a school or some sort of municipal building. Tough to be sure, but whatever it was, it had clearly taken the brunt of a very large assault, as all that remained were two partially intact walls and several enormous rubble piles at the bottom of which lay who knew what, a question no one much cared to ponder. Best we could tell from our sporadic radio communication, the group we were endeavoring to meet was entrenched a few hundred yards beyond this building.

The clearing extended more or less indefinitely to our left and right and there was no immediately apparent way around it. We were hunkered down in the remains of a shattered restaurant, and in that moment the quiet suddenly became quite jarring. We were all experienced soldiers by this point, and everyone knew where the situation was headed. No one wanted to be the first to say it out loud though, so after several moments of uncomfortable silence and eye contact avoidance, I cleared my throat and said what needed saying.

“Gentlemen, I am prepared to discuss with you my plan for moving this thing forward, but it is a bad idea, and so I would like to have the opportunity to hear anyone else’s bad ideas first,” this last bit of wit meant simply to lighten the grim mood that had befallen the group. The only good option, though no one was crass enough to articulate it, was to say screw the other unit and return whence we had come that morning.

“I expect tunneling is out,” one of the fellows said, doing his best to muster a grin.

No one else laughed or even attempted a smile. And no one had any other ideas to put forward—good, bad, or otherwise—despite the long minute of contemplative silence that ensued.

“Then here’s the deal,” I continued, doing what I could to sound decisive, though I certainly didn’t feel that way. “We’ve no earthly idea what’s between us and that building across the field, but we damn well need to find out if we’re to have any hope of reaching the other unit. Way I see it, there’s two main possibilities out there—land mines and snipers. If it’s mines you’re worried about, you pick your way, slow and methodical. If it’s snipers, you run like hell. That, gentlemen, is what is known in military strategy circles as a conundrum.”

I paused for a second to gather my thoughts and to allow the others to do the same.

“We don’t know what’s out there, but I can sure as hell tell you one thing. If we all go together, we’re fish in a barrel, for snipers or mines. If it’s just one, he’s a small and mobile target. What I propose is that one goes, and takes with him a pack of medical supplies. Whatever happens, at least we’ll know better what we’re dealing with between here and there, and we can make a whole lot more informed decision for the others. That’s a pretty shitty deal for one of us, but unless you’ve got something better, that’s the way I see it.”

More silence. No alternative suggestions.

“I’ll take your silence as grudging agreement, which leaves only the unpleasant matter of who it’ll be. There’s two choices—volunteering and drawing lots.”

One more tense moment and no hands raised. There was no faulting the men over bravery. They were simply spent and dispirited and that was the long and short of it. It also occurred to me, as I sat waiting, that maybe the hardest part of this whole affair was deciding whether to run or take your time. Matter of personal preference really.

“Right then,” I said, a bit too loudly. “Lots it is.” I reached into my pack and extracted a filthy sheet of paper, tearing it into sixteen thin strips. “I’m ONE, Biggs here is TWO,” I said, gesturing to my left, “and so on around the circle. Write your number twice and then tear your scrap in half.” I sent the paper fragments around with a pen, and they complied in abject silence. One-in-sixteen would have seemed pretty favorable odds under most circumstances, only this wasn’t most circumstances. After a moment or two of silent scribbling, I removed my hat and sent it around in the same direction.

“One goes in. One you keep,” I said.

The hat had made its silent way past twelve of the men and was in Bates’ hand where it remained for a moment longer than seemed necessary. In that moment a strange look came across his face and he flung the hat violently back in my direction, scraps of paper drifting about like a snow flurry.

“Aw, FUCK your damned numbers,” he said with a mad smile, before the paper scraps had even finished fluttering to the ground. “I’m going. Ain’t none of you can run worth a shit anyway.” He stood, turned, and made his way without further comment to the large bag of medical supplies.

Hell if I knew why, but I felt the need to say something. “Bates, c’mon…” I wasn’t even sure what I was trying to convey. I stood and walked to where he was already taking items out of the med kit and loading them into his pack.

“Look,” he said, not bothering to turn to face me, “there’s no other way, right? You said so yourself. So here’s how it goes. I run like a madman on fire across that field—thirty seconds max. I dodge and weave, keep the snipers guessing. You keep an eye on my path so if I happen to find a mine, you know where there’s likely gonna be others. I get across, I find our boys just past the school. Piece of cake, right?”

There was no point arguing the matter. “Look…Bates…If they’re shooting, it’s gotta be straight on from the school or back to from somewhere near here. We’ll cover you best we can from this side. Pull your pack up tight and you’ll have a bit of protection from any rearward shots. And keep moving about, yeah? We’ll give you a few minutes once you make it over to find the other unit. Give us a call on their radio, we’ll be right behind you.”

“Sounds like a plan, man,” he said, hoisting the laden pack onto his back. “No time like the present, eh?” He stepped past the still silent group and toward the front of the building. There were murmurs of encouragement from the group but no one rose. The more routine the whole thing felt, the better, I guessed. No handshakes, none of that. I gestured to two of the men. They rose, grabbed rifles and joined us out front. We talked briefly and the two departed for positions from where they could best offer Bates a modicum of covering fire if the need arose. It was a dubious comfort and we all knew it. Covering fire assumed the ability to identify the precise position from where a sniper shot had come, which was a decidedly dodgy proposition. Still, it felt better to be doing something and the two seemed grateful for the opportunity. I withdrew my map and pointed to a spot beyond the destroyed school that was our best guess for where the unit was located.

“Give us a shout when you’re in,” I said. “If their radio doesn’t work, send up a flare or something. It’s a hell of a thing you’re doing, man,” I offered.

“Hell of a stupid thing,” he replied, still bearing that slightly mad grin. “Just like the two hundred in high school track. No problem.” He turned to face the open field and began to breath rapidly, steeling himself. “Remember, you keep a good eye on my track now.” In the instant before he broke for the field he lifted his right hand, withdrew something small from his shirt pocket, and flipped it over his shoulder in my direction without looking back. “Hang onto that for me, will you?” he said, and off he went, sprinting hell for leather, the pack bobbing wildly upon his back.

There were no sounds now, save for the blood rush in my ears, the receding thud of his steps, fast and hard upon the ground, and the sough of a cool breeze that had turned the day rather pleasant, circumstances notwithstanding. Bates moved across the field like a man possessed—left, right, pulling up occasionally, then leaping violently forward, all in an attempt to present as difficult a target as possible. He stumbled once, but it appeared from a distance to be his own doing, a poor piece of footing on the rough terrain. But he was up again and nearly there, fifty yards remaining. And then there came a crack, a single note from the far side of the field that did not reach my terrified ears until what seemed an eternity after I’d already seen Bates go down on one knee and stay there for far too long. Only then he rose again and took a slow step, then another, almost seeming to regain his conviction, if not his original pace. He managed a jog to the right, then another feint to the left before a second sharp crack carried across the field. Bates went back onto his knees and he did not rise again. Through the glasses it looked as though he turned and looked back in our direction one brief time before falling forward not ten yards from the far edge of the field.

I watched in shock for what seemed hours before being jarred back to the moment by the distant rattle of automatic fire. There came several short bursts and I saw the puffs of ricochets off masonry from the peak of a tower some fifty yards to the left of where Bates lay. Someone in the other unit had drawn a bead on the sniper and was returning fire. Seconds later a grenade was launched into the same tower, and with a flash and dull thud it was over. As I continued watching through the glass, a figure appeared from behind a pile of stones adjacent the school, gesturing wildly that we should make the crossing. On what degree of intelligence that gesture was based I could not say, but I signaled back, assuming they had binoculars as well, and turned to make my way back to the rest of the group.

Later that afternoon, after we’d compared notes with the other unit on troop movements and known or presumed regime locations, and had tended to the soldiers who needed medical help, we sat about the encampment, smoking, eating rations, and not talking much. A couple of volunteers went out onto the edge of the field and retrieved Bates’ body, which we tended to with as much reverence as we could muster, burying him in a berm behind the bombed-out school. As the men settled in for the night, I found a spot well removed from the others and pulled Bates’ small book from my pocket, for that was what he had tossed to me just before his dash across the field. I would read carefully all hundred and thirty-eight of the names and accounts before the night was over, and as I turned the pages, it became clear, as I’d noted over Bates’ shoulder the previous night, that, indeed, every page was identical—name, rank/position, age, hometown, cause of death. I also discovered upon careful scrutiny, just what the small dark smudge in the lower corner of each page was. Some were randomly shaped, some were quite clearly fingerprints, presumably of the man himself. And each mark was rendered in the man’s own blood, for despite the aged dark brown tincture of each stain, there was no other possible explanation. He had been close enough to every man, killed or wounded, to make a signature in blood upon his page in the book.

And as I made my way slowly through the names—a few I knew, but most I did not—I came at last to the final page, upon which was written Bates’ own name, in precisely the same format and handwriting as all the others. There was his rank, age, hometown, all of it, even a still reddish blood fingerprint, though when he’d had the opportunity to make it was unclear. The only difference between his entry and all the others was a blank space where cause of death belonged. Without a moment’s thought or hesitation, I withdrew my pen and wrote neatly ‘Sniper fire’ in the appropriate spot. Then I closed the book, replaced it in my shirt pocket, and lay back to rest.