It always happens the same way. He stands tentatively before the marble fireplace and gazes into the painting for a few moments, wondering who created it (no signature) and when they did so (at least a hundred fifty years ago, that much is certain). Surprisingly, he long ago ceased wondering how the miracle itself works. No point speculating, he supposes. It’s a wondrous, impossible bit of sorcery, or perhaps arcane physics, in either event a thing he can never hope to understand. But he’s made the journey now several times, and it’s always the same, regardless of direction. The discovery was a complete fluke, or at least he imagines that it was. He had stood in this very spot, alone in the room, reached out his right hand, and placed a trembling fingertip on that face near the left margin of the picture, the face so tiny yet so terribly clear. He was by now used to what followed, but that first time had really been something altogether extraordinary. The moment his fingertip had brushed the spot on the canvas, there had come a brilliant light, like a slightly elongated camera flash going off in your face, and then it was gone and he’d found himself standing in the same spot, in the same house, staring as before at the same painting, but with a completely different family, and in a time slightly more than one hundred years before that in which he had been born.

It always happens the same way. He stands tentatively before the marble fireplace and gazes into the painting for a few moments, wondering who created it (no signature) and when they did so (at least a hundred fifty years ago, that much is certain). Surprisingly, he long ago ceased wondering how the miracle itself works. No point speculating, he supposes. It’s a wondrous, impossible bit of sorcery, or perhaps arcane physics, in either event a thing he can never hope to understand. But he’s made the journey now several times, and it’s always the same, regardless of direction. The discovery was a complete fluke, or at least he imagines that it was. He had stood in this very spot, alone in the room, reached out his right hand, and placed a trembling fingertip on that face near the left margin of the picture, the face so tiny yet so terribly clear. He was by now used to what followed, but that first time had really been something altogether extraordinary. The moment his fingertip had brushed the spot on the canvas, there had come a brilliant light, like a slightly elongated camera flash going off in your face, and then it was gone and he’d found himself standing in the same spot, in the same house, staring as before at the same painting, but with a completely different family, and in a time slightly more than one hundred years before that in which he had been born.

Having worked and saved assiduously for the first five years following university, Stephen Fleming had married his high school sweetheart Bethany Brooks, and promptly set about shopping for the ideal home in which to begin their new life. The only constraint in the search was that Stephen’s teaching position at the university obliged them to remain in the southern Maine area, what with positions in his field being so rare and difficult to come by. They had looked at perhaps half a dozen homes with the help of a realtor friend Bethany knew, and then one day stumbled across an interesting prospect on their own while out driving through neighborhoods near campus. Stephen would later tell friends that the place had almost literally called out to him as they had driven by. They hadn’t even noticed the ‘For Sale’ sign until they’d passed and Stephen had felt an odd premonition, stopped, and backed the car up. Later that day, after a call to the listing agent, they had toured the house, and by dinnertime that evening signed a contract. In the traditional haste of a realtor’s walk-through, neither Stephen nor Bethany had paid any special attention to the painting that hung above the living room fireplace. It seemed an unremarkable scenic depiction, part of the furnishings of the previous owners that would disappear along with that family’s other belongings when they departed. Except that it didn’t.

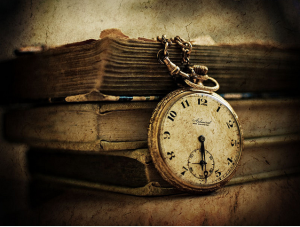

They closed on the Bentley Street house five weeks later, and Stephen proudly brought his new bride home. It was only after they had each carried several armloads of belongings inside that they noticed the painting was still hanging in its original spot above the fireplace in the now otherwise empty living room. They were delighted and a bit perplexed to discover that the previous owners had left it behind. After numerous fruitless attempts to contact them, the couple had given up and elected, for the moment at least, to leave the painting in its original spot. After all, they had nothing better to replace it with. They were consumed in those first few days with getting situated in the new home, but they did take a moment after sunset of the first day to stand together and consider the artwork.

At first glance, it was nothing special; certainly no secret garage sale Van Gogh or Renoir had fallen into their possession. It was a traditional bucolic scene that included a farmhouse with adjacent barn, a great spreading oak tree, and a front lawn upon which several characters stood and appeared to converse in small groups. It had the look of an informal neighborhood gathering, and the figures, perhaps a dozen in all, were dressed in the distinct late 19th-century, New England style. The place could have been anywhere, though the color and style of the house and barn, like the dress of the picture’s inhabitants, suggested southern New England. The painting was not overly large—perhaps four feet wide by three tall. Aside from the overall scene, the thing that struck both of the Flemings in that first cursory viewing was the quite extraordinary level of detail. This was no broad-brushstroke impressionist piece. You could make out very tiny nuances wherever you looked, and the faces, despite being tiny, were clearly different one from another. Only later would it become apparent just how different.

Nearly seven weeks of normal moving in and acclimating passed before either Stephen or Bethany had any occasion to again give the painting more than a passing consideration. It was a Saturday and the couple at long last had a weekend when they didn’t feel compelled to do anything of much consequence. Stephen lay supine upon the sofa, enjoying a few hours of mindless television. Bethany was in the kitchen, humming quietly, her pleasant tones interrupted periodically by the strident shriek of beans being ground for coffee. And then, for no particular reason that he would later recall, he lowered the volume on the television, rose from the sofa, and stepped to the fireplace, its mantel now littered with the Flemings’ own bric-a-brac. And there he stood for a full minute, actually giving the painting a good bit of serious scrutiny for the first time. The paint surface was smooth and glossy, and it had that faint crackled effect that oils get after a long time, The more Stephen stood before the thing, the more he found himself wondering if perhaps they had indeed fallen into something that might be worth at least a bit of money. It certainly merited a phone call or two. Again fascinated by the detailed brushstrokes, he moved his face to within inches of the painting, removed his glasses, and began to study the characters. In that moment, he noticed that one of the revelers near the farmhouse bore a striking resemblance. It was his own face, clear as day.

The figure was not a participant in any of the groups, nor even part of one of the couples. It was, in fact, the only figure in the picture standing alone, seeming to reflect pensively on something about the oak tree that grew near the front left corner of the house. One hand was in the man’s pocket, the other raised to his chin in apparent thought. The figure looked out of the painting at about a three quarter angle, but there was no mistaking the resemblance—the round face, the copious chestnut hair, the thin, aquiline nose, and even the slightly greater girth than Stephen was comfortable with, but which he was already having an increasing difficult time managing. It was all quite striking, even borderline disturbing. As he continued to stare at the figure in the painting, he made a mental note to solicit Bethany’s opinion when she returned from the kitchen. And then, as an innocuous parting gesture before returning to the television, he reached out a tenuous right index finger and brushed it lightly over the figure. With that simple action his life changed forever.

It was the faintest of touches, the most innocuous of acts. There were no auspicious clock chimes or distant rumbles of thunder outside, no indications of anything portentous. Nothing more than the quickest of strokes—his right index fingertip touching the glossy surface of the painting, precisely upon the face of the tiny character that so resembled him. But in that instant there had come a momentary flash, so bright but fleeting that afterward he found himself doubting it had taken place at all. But it had. For when he drew his finger away from the painting, lowered his arm to his side, he noticed immediately that the smell of the room was different. Where there had been nothing notable before, there now wafted through the living room the unmistakable odor of baking bread. Bethany was a decent enough cook, but she only infrequently dabbled in baking and had not done any since moving into the new house. It was while he was pondering the oddness of this sudden sensation that he also began to perceive a new strangeness about his surroundings. The painting hung as before, though he was still standing close enough to notice that the fine cracks he had noted earlier in the glazed oil seemed now to have vanished. It was clearly a hallucination of some sort; perhaps he had looked at it wrong before. The surface of the painting looked now to be unblemished and quite nearly new. Far stranger, though, was the unfamiliar array of objects that stood before him on the mantelpiece. Stephen closed his eyes hard for a couple of seconds, opened them again, but the mantel was still that of someone else’s home.

There stood before him now a collection of fine antique china figurines and two large brass candlesticks where before had rested the couple’s decidedly more prosaic collection of DVDs, an iPod charging station, and a short row of paperback books. As confusion began to give way to fear, he took a step back from the fireplace and turned slowly to his right. It was the same living room, the same windows, doorways, thick crown molding, and wide oak flooring. But everything else—the furniture, wall hangings, curtains, rugs, and chandelier—were from a bygone era. He was no historian, but it all appeared to have been lifted directly out of the late portion of the preceding century. It was as though he had been instantly, miraculously transported from modern New England to the home of Henry Longfellow or Nathaniel Hawthorne. Stephen suddenly felt a coldness well up inside and, fearing that he was in the midst of a stroke or other hallucinatory episode, turned to make his way to the nearest chair, one of matching pair of wide elegant wingbacks that stood before the fireplace. Before he could sit, an unfamiliar female voice arose from the kitchen.

“Stephen, dearest,” the voice called. “Are you quite ready for supper?”

He made no response, only continued his descent into the plush chair. Continuing his surveillance of the living room, the sudden and utter unfamiliarity of it all caused the coldness in him to morph quite quickly into a sweat of the sort familiar to those prone to panic attacks. He made a feeble and futile attempt to wipe a shirtsleeve across his brow. He had never passed out even once in his life, but he suddenly felt as though his first time might be fast approaching.

“Stephen, Margaret has made your favorite—pork chops and apple sauce. It would be terribly rude of you to let it get cold.”

A face appeared around the corner of the entrance that led into the dining room. It was a beautiful petite woman in her early twenties, hair pulled back and secured tightly at the back of her head. Her dress was of an antiquarian pattern absolutely in keeping with the decoration of the living room, right down to the delicately frilly collar around her neck.

“Stephen, gracious!” she exclaimed, rushing into the room at the sight of the man who appeared on the verge of unconsciousness. “Whatever has come over you?” She placed a hand on his brow and he was too overcome with whatever was happening to resist, despite having no knowledge whatsoever of who the woman might be. Something in his life had come suddenly, violently unhinged, and the only two anchors tying him to reality at the moment were the painting that still hung above the mantel and the fact that, indeed, pork chops and applesauce were his favorite dinner, though how this strange but remarkably beautiful woman could possibly be aware of that fact eluded him completely. She took his hand and looked into his eyes with great tenderness and concern.

“Stephen, dear, whatever has come over you? Have you had too much to drink before dinner?” She rose in sudden confusion and stepped back, gazing down at him in apparent confusion. “Heavens, you’re perspiring like the dickens.”

Thus far he had uttered not a word in response to her questions and exhortations. He released her hand involuntarily and rose with difficulty from the chair, then strode uncertainly across the living room to one of the large front windows that looked out upon the street. In an odd way that he couldn’t begin to explain, he found himself not at all surprised to see his car-filled suburban neighborhood street replaced by a cobblestone boulevard down which several horse-drawn carriages made their way, their faint hoof claps creeping through the glass and into his astounded ears. He fell into a different chair, uttering a faint and plaintive moan upon noticing for the first time, the clothing he was wearing. He looked as though he’d only just stepped from out of a Dickens novel.

“Goodness, Stephen,” the woman said, raising a concerned hand to her lips. “You look as though you’re about to pass out. Shall I send Margaret around to fetch Doctor Colson?”

“No … no, just give me a moment,” he replied, gathering himself with monumental effort. He rose slowly and walked toward the fireplace, stopping once more before the painting, looking again upon the figures in the scene, his eye finally alighting once more upon the lone figure standing beneath the great spreading oak. His initial reaction was to reach out and touch the painting’s surface once again, but he found in that moment that a part of him was suddenly keen to deduce just what it was that had occurred and where he was now.

“Ma’am,” he said, haltingly, turning from the painting to face the delicate woman who remained by the window looking toward him with apparently great concern. “Kindly indulge me, as I am feeling a bit … off, as you have correctly observed. Remind me … goodness, this is going to sound like a startling thing … remind me of just who you are and why you are in my home … please.”

A look of shocked sadness came over the woman’s face and she stepped in Stephen’s direction, stopping a short distance before him. Considering him silently for a brief moment, she crossed her arms tightly and her mien changed suddenly to one of feigned annoyance.

“Stephen, if this is your notion of some sort of joke, allow me to disabuse you of its humor.” She paused briefly, allowing for a retort of any sort. Receiving none, she continued. “My father said long before we married that he felt you were possessed of an unusual, possibly even inappropriate, sense of decorum. I’m beginning to wonder if perhaps he wasn’t correct in his perceptions.”

Just as the implications of the word ‘married’ were beginning to sink into Stephen’s already confused mind, a stout black woman glanced around the corner of the doorway.

“Mr. Fleming, Mrs. Fleming, will you be dining now or shall I put the supper on to warm?”

“No, no, Margaret, we’ll be along directly,” the woman said. “Stephen is just … collecting himself.”

She extended a hand in Stephen’s direction, her face returning to its original concerned but entirely beautiful look. Without the slightest idea what to say or do in response, he extended his own hand, accepted hers, and allowed her to lead him into the dining room.

As with the living room, there was nothing in the dining room with which Stephen had the least familiarity, aside from the shape of the room itself, the window placement, and the wide boards of the hardwood floor. Also like the living room, everything here—the furniture, the dishes, the rugs—was the most pristine of antiques. In response to the woman’s gesture, Stephen seated himself uncertainly at the head of the table. He gazed for a moment upon a wondrously displayed feast of pork loin, vegetables, and fresh bread. Only then, suddenly once more overcome with another wave of coldness, he pushed back his chair, rose, and nearly stumbled as he stepped to the front window, looking out again upon the cobblestone street and the passers-by. It was well into dusk and a man was making his way down the street lighting gas lamps one after another with a long pole. Never before could he recall having seen so many men wearing hats.

“Look … I’m sorry…” he said, turning from the window and facing the woman who sat in stunned silence at the table. “I fear I must beg your kind indulgence for a moment…” and even as the words in their unfamiliar diction departed his lips, he paused, confused as much by his own peculiar tone as by the profound and sudden twist in his surroundings.

“What I mean to say is …” he took one cautious step toward the table, then stopped again. “Please do not take this in the wrong manner, but something is terribly amiss … I confess that I … I have no earthly idea who you are. Nor do I understand what has happened to my home or, indeed, to myself.” He raised both arms slightly, palms outward, the gesture intended to encompass the room or perhaps his entire life.

A look of shock came over the woman. She sat unmoving for one further moment, simply staring up at Stephen. Then she leapt from her seat and stepped briskly toward the kitchen door.

“Margaret!” she shouted into the kitchen. “Please drop whatever you are doing this instant, and run round and fetch the doctor … yes, this very moment. Mister Fleming has had an accident of some sort and requires immediate attention.”

Five days and three visits from Doctor Colson later, Stephen lay on the living room sofa, one hand spread upon his own silk-clad breast, the other warmly ensconced between Penny’s two hands. Penny, who had not left his side since what she and the doctor had determined to be an attack of some sort, but a most peculiar one that had thus far admitted no rational explanation. Penny, who after much discussion and the temporary suspension of all disbelief, had turned out to be Stephen’s wife of nearly five years—five years that had commenced on May thirty-first in the year eighteen hundred and eighty three. Despite the five days of acclimation and much discussion concerning just what might have caused such a catastrophic loss of Stephen’s memory, the cause of his amnesia remained an absolute mystery, for he seemed fine in every physical sense.

“Penny, it is simply the strangest sensation. I have never experienced anything quite like this.” He spoke haltingly, uncertain of just what he was trying to express, but not wanting to frighten this woman—his wife—any more than he had already done.

“I tell you, I feel as though I am walking about in an impenetrable fog. And it is only through your unceasing ministrations that I may at last be approaching a state of some clarity. I recall a bit more about you and I and … and … our marriage. I have some recollection of purchasing this home, at least I think I do. I remember thinking it odd that the previous owners departed leaving behind the painting … that one there.” Stephen lifted a hand and gestured toward the fireplace. Whether he truly did recall any of these things was far from clear, but he could honestly say that he was growing slowly more acclimated to his astonishing new situation.

“Yes, Stephen,” Penny replied. “Yes. Oh, thank Heaven you’ve not lost everything. Doctor Colson says that if we work together, recall things in small doses, we may get you back to normal in short order.” She handed him a glass of water.

“He’s never encountered anything like it. He says it’s the sort of condition one expects to see after an accident or a blow to the head, but that to lose so much without any evident cause is really quite extraordinary. But yes, you’re entirely correct about the painting. We spent some considerable effort trying to get it returned to the previous owners, but it was all for naught. They’d simply vanished into the ether.”

Stephen handed the glass back and endeavored to sit up on the sofa.

“Are you certain, Stephen? The doctor says you should just concentrate on resting and regaining your strength.”

“I appreciate your concern, Penny,” he replied. “I genuinely do, but if I lie here another moment, I shall go stir crazy. And besides, who knows? If I were to fall and crack my skull, well perhaps it would all come back to me that much faster.” He managed a wan smile as he sat up, staring for an additional long moment at the painting.

“Oh, Stephen, don’t you dare joke about such a thing. You sit right there for a moment and I shall have Margaret make you a cup of tea.”

“Thank you, dear. Thank you. That will be wonderful.”

Penny stood and left the room, gazing back at Stephen uncertainly as she departed. A moment later he could hear quiet discussion emanating from the kitchen. He rose from the sofa and made his way to the fireplace, where he stood for several long moments considering the painting, its hold on him by this point nearly magnetic. It was the same as it had ever been—the bucolic scene, the figures frozen in time, the lone man beneath the sprawling oak tree, removed from the others. But then, was he really the same? Truly? He found he could not now recall the precise expression the man had borne when first viewed. And who could tell, truth be told, for the image was so very small, the face scarcely more than a pinpoint. He remembered how much the figure had looked like him when he’d first examined it an eternity ago, and that look had certainly not changed. But the expression, the expression did not seem quite familiar. More importantly, it did not now seem appropriate to the overall feeling of the scene. For all of the other figures in the painting were either turned away or, if facing outward, bore miens of neutral equanimity whereas this man, alone, looked for all the world as though one side of his lip (could you really perceive a lip in an image so miniscule?) was curled upward in a knowing smirk. In an act that now seemed both impulsive and inevitable, Stephen slowly raised his hand toward the painting. In the exact moment that his fingertip touched again upon the lone figure, Penny entered the room carrying a cup of steaming tea.

“Stephen…Stephen!” Bethany said, her voice clear and possibly slightly concerned. “Are you okay? You glazed over there for a second.” She stood in the entryway that separated the living room from the dining room, holding in each hand a steaming cup of fresh coffee. “Have a sip of this,” she said. “You’ll love it. It’s Brazilian.” Her remark was punctuated by the sound of a car horn from the street outside, and then the wail of a distant siren. He turned his gaze away from the painting and briefly toward Bethany, then about the living room, the tasteful modern furniture, the large television, and back to the DVDs and books along the mantel. He quickly but unsteadily made his way to the sofa and fell heavily onto it. He said nothing for a moment, focused instead on simply collecting himself.

A month passed, then another. Stephen quickly grew used to the bizarre twist his life had taken. And as he experimented with the insane power of the painting above the fireplace, he learned what he could about how the thing worked. Nothing about it made any sense, and yet there were rules, restrictions on what he could and could not do. He discovered these by making what he came to regard as ‘the journey’ many times in the ensuing weeks. His visits to Penny’s nineteenth-century home (which was, of course, his own home as well, though he struggled still to wrap his head around that extraordinary notion) could be as brief as an hour or two, as long as a month. In every case, the transition from 2014 to 1890—or the reverse—required nothing more than the brush of a fingertip upon the visage in the painting, the face he had by now come to regard as his own. And in each case there would come the brief, bright flash, the momentary disorientation, followed by the realization that he had, at a stroke, either shed or gained nearly one hundred twenty years, and without moving so much as a step.

The first important thing he learned was that this astonishing power was his and his alone. In the brashest experiment of all, he had, without any attending explanation, exhorted Bethany to place her own finger upon the correct spot in the painting. He had sighed audibly with relief when nothing at all happened save for her look of uncertainty at his request. Then, repeating the experiment with Penny, the result had been the same. Perhaps the most surreal aspect of the entire experience was the realization that while he was ‘away,’ no time whatsoever appeared to transpire in the place/time that he left behind. He could depart one moment in time, live for a month or more in the other, and when he returned, it was as though he had merely blinked. Even if one of the women—one of his two wives, though this too was proving a troublesome though not entirely unpleasant concept to grasp—was standing next to him when he transitioned, the most reaction he received upon returning hours, days, or weeks, later was the perception that he had spent a second or two daydreaming.

It quickly occurred to Stephen that enormous pecuniary benefits might accrue from his new situation. In fact, it appeared there could be opportunities in both directions. Certain knowledge of future events presented obvious opportunities while residing in the late nineteenth century—final scores of yet-to-be-played sporting events, trends in stock prices. Similarly, easy access to laughably inexpensive rarities in the previous century afforded the chance to sell them for vast profits in what he still could not help but regard as the ‘present day,’ though the notion of the ‘present’ was fast becoming an ephemeral one. This latter, though, carried its own set of complications. For one of the rules he had discovered in the early going was that he could not transport material objects in either direction. Even the clothes he wore were left behind, replaced upon arrival with whatever he had been wearing on his most recent previous visit. Given the absurdity of the entire situation, he couldn’t help but regard these limitations as altogether capricious, but he was nonetheless constrained by them. Only then, an interesting workaround had occurred to him, one that he promptly tested and found to be as simple as it was magnificently successful.

Stephen had learned, as part of his original purchase negotiations in 2014, that the Bentley Street house was in excess of two hundred years old, meaning that even in 1890 it was well along toward its first century of existence. It was a surpassingly solid structure and it had, in the old New England tradition, a cellar whose walls comprised large stone blocks—blocks Stephen imagined hadn’t had reason to be moved in the entire two centuries of the home’s existence. And so it proved.

Being a bit of a bibliophile, he could only wonder at what a flawless first edition from the turn of the nineteenth century might fetch in the early twenty-first, if only the transition could be performed. He considered the possibility of placing objects in bank safe deposit boxes during his visits to Penny, but he had to wonder what a bank’s policy might be on items unclaimed for more than a century, particularly if the bank itself were to relocate or become defunct. But there was, he thought, one secure place whose future condition he knew only too well, and that was the house itself. Which is how he came to find himself one day in the autumn of 1890 in the cellar—Penny having stepped out to visit a relative across town—struggling with hammer and chisel to remove one of the large square stones in the center of the basement’s rear wall. With great effort and more than a few bruises, he at last extracted one of the great stones, setting it awkwardly upon the floor to reveal the layer of soil behind. Into this he then dug a deep recess, creating, in essence, a safe into which objects could be placed for future retrieval. Recognizing that whatever was placed there must be expected to survive over a century of waiting (time travel the hard way, he thought with a smile), he took steps to create as tightly sealed an enclosure as he could manage, forming a small vault of concrete that he could seal against the elements or accidental discovery simply by replacing the stone in the wall and lightly remortaring the seams.

Having thus satisfied himself as to the imperviousness of his time capsule, he ventured out to the nearest book shop, where he purchased, for the miserly sum of seventy-five cents each, three brand new copies of the first printing of Huckleberry Finn by the newly popular author Mark Twain, the novel having been first published only five years earlier. He took great pains to protect the books with several layers of heavy oilcloth, and then he enclosed them inside a heavy wooden box and placed the entire affair inside his makeshift safe. Moments later, following a quick trip up the cellar stairs, a bit of cleaning up in the bathroom, and a return to the painting, it was 2014 again and he was back in the cellar, holding in his astonished hands the books that had lain safely hidden for one hundred twenty years but which looked as though they had only just come off the printing press, books which at 2014 rare book prices, were worth nearly a quarter of a million dollars each. When he showed one of the books to Bethany, he spoke only of his good fortune at having found such a priceless volume in an unnamed estate sale while visiting friends in coastal Maine. In the days that followed, this process worked equally well with small antiques, jewelry, and even precious metals.

And so it came to pass that, by judiciously combining these periodic antiquarian purchases with a number of strategic very-long-term stock investments, Stephen and Bethany (and Stephen and Penny) became extraordinarily wealthy. But, despite in both cases their newfound ability to purchase a far larger and more prestigious home—which they did, along with vacation homes in the Maine coastal town of Camden, in Paris, and elsewhere—Stephen made certain that they never parted with the Bentley Street property, citing its sentimental value as the couple’s first home. In the final several years of Stephen’s great adventure, he found he was spending ever-greater periods of time with Penny. He had become as enamored with her as he had ever been with Bethany, indeed rather more so, and the combination of effortless affluence and two unsuspecting spouses had proven impossible to resist. It eventually grew into an entirely astonishing decade, by any objective measure. Except that, approaching his thirty-fifth birthday, Stephen couldn’t help but notice that in recent weeks he had been feeling unusually tired and was experiencing a series of unfamiliar muscle aches. As with all young men, Stephen had eschewed nearly all medical attention to this point in his life, and it was only at Bethany’s insistence (his obvious assessment being that modern medicine surpassed the nineteenth-century sort) that he made an appointment for a routine physical. He was, after all, at thirty-five if not exactly an old man, certainly no longer a teenager.

“Have you been on any medication?” the doctor asked, staring at Stephen from behind his office desk, “or taken part in any unusual medical procedures?”

“Unusual?” Stephen replied with an uncertain expression. “How do you mean exactly?”

He had come alone, with the promise of a full report to Bethany when he returned home.

“I ask only because quite a number of your test results show rather odd results and I’m at a bit of a loss to explain them,” the doctor said. “When’s the last time you had a physical?”

“I’m afraid I’m embarrassed to confess that I can’t actually answer that question, as I don’t recall.” Stephen said. “Suffice it to say that it’s been a very long time.”

“Quite so, Stephen. Well, here’s the nut of it. I’ll share the detailed results with you in a moment, but the short version of your condition … your state … is that I at first found your assertion of age to be altogether unbelievable. So much so that I took the liberty of going back into the public record and pulling up your birth certificate.”

“I might have saved you the trouble, Doctor. Here it is on my driver’s license—date of birth, April seventeen, nineteen eighty-nine. But why in God’s name would there be any question about that?”

The doctor hesitated, rose from his desk in momentary silence, and stepped to the office’s back window, where he gazed out for a moment in silence.

“I don’t quite know how to say this, Stephen. On paper you’ve only just achieved your thirty-fifth birthday. The thing of it is, every indication is that you have the physiology of a sixty-five-year-old. We’ll have to do further analyses of course, but your initial test results suggest the onset of osteoporosis, arthritis, and, most serious of all, you’ve tested positive for early Alzheimer’s.”

Stephen sat in stunned silence as he digested the doctor’s words.

“Is there a history in your family of anything at all like this?”

Stephen sat for a moment longer as though he’d not heard the doctor’s question.

“No, nothing like that at all,” he suddenly said, startled from his momentary reverie. “Men in my family just pretty much die of old age. No cancers, no heart attacks … nothing. They just sort of … wear out. My grandfather’s still alive and he’s well into his nineties.”

The doctor returned to his desk for a moment and opened a thin file folder. Consulting it for a moment he retook his seat.

“Stephen, have you ever heard of something called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome—HGPS?”

“No, afraid you’ve got me stumped there. Is that the name for my situation?”

“I don’t know,” the doctor replied. “Medical people typically refer to it simply as progeria. It’s extraordinarily rare, less than one case in five million people. Thing is, it always manifests in newborns. Affected children begin aging rapidly from birth and rarely make it past their thirteenth birthday. And besides, it screens very clearly in genetic tests, but we see no trace of it in any of your results. We’ll need to do a few more tests of course.”

“I understand,” Stephen said, even though he didn’t, but because he couldn’t think of anything else to say. “So what are the implications of something like this? Is it … is it fatal?”

“Well, first we’ll want to see if that’s what we’re dealing with before we make any rash assessments about prognosis. But the condition itself is not fatal in itself. It’s just that it causes a far more rapid onset of all the normal manifestations of old age—osteoporosis, weakening of the heart, dementia. People affected with progeria don’t die from the disease per se. They die sooner than they should from the advanced old age that it brings about.”

“And can anything be done?” Stephen asked. “Is there any sort of treatment?”

“Thus far no, I’m afraid, though there are, of course, any number of ways of addressing the resulting symptoms. As rare as progeria is in its documented form, I’ve never once heard of a case in which the condition appeared absent any apparent genetic underpinning. Nor are there any documented cases of the disease showing up later in life rather than from birth. It’s almost as though you’re aging at twice the normal rate, whereas progeria patients experience something more like ten times the normal aging rate.”

In that moment, when the doctor uttered the phrase ‘twice the normal rate,’ it all suddenly and violently became clear to Stephen, though for reasons he couldn’t possibly explain to his physician. Despite the fact that his journeys from Bethany to Penny and back consumed no real time in the era whence he departed, his biological clock had nonetheless continued advancing at the normal rate regardless of his location in time. It was yet another rule governing the painting’s power, a particularly cruel one that was only now apparent with the benefit of hindsight, and one about which he could do absolutely nothing.

“You know,” the doctor said, “there’s another strange aspect of this case, perhaps one that’s the very oddest of all. Despite all of your physiological results showing what appears to be a relatively advanced age, cosmetically there’s very little unusual at all with you. The progeria patients—what few there are—show very marked traits that make them relatively easy to identify even prior to genetic testing. They actually look as though they are aging, whereas you, aside from a bit of graying around the fringes of your hair, appear more or less normal for your documented age. Most unusual. Not that it’s of any great comfort to you, but I expect there will be a fair bit of research and interest in your case.”

“Perhaps they’ll actually name a new syndrome after me, eh?” Stephen said, managing a thin smile.

“Not necessarily the most desirable way to achieve immortality,” the doctor replied. He rose once more from his chair. “I would like to schedule a time for some future tests, if you’re willing. And I’d like to ask one more favor of you, if it isn’t too impolitic. Would you be so good as to begin keeping a journal about this situation? How you feel, any changes from one day to the next, that sort of thing. Though it’s admittedly late in the game, it would nonetheless benefit any future analytical efforts to have a first-hand account of how your condition is proceeding.”

In the weeks that followed, Stephen, feeling that the damage had by now been largely done already, continued visiting Penny regularly. Also, as an experiment that he felt could do little in the way of additional damage, he determined to seek out a second opinion during a visit to Penny, to subject his condition to the diagnosis of nineteenth-century medicine. To his immense surprise, the hundred and twenty-year gap notwithstanding, the diagnosis was nearly identical, the only material difference being that the progeria syndrome had only been identified in the preceding decade and the two physicians for whom it was named were both still alive and actively practicing medicine. Stephen’s case was unique enough in the late nineteenth century so that a consultation was arranged with one of the two original discoverers of the condition, Sir Jonathan Hutchinson himself, an English physician who happened to be visiting Boston around the time. The famed doctor, following a detailed examination, agreed that extraordinarily advanced aging was occurring in Stephen, but declined to classify the case as one of progeria, most of the principal manifestations being absent in this newest case. It was, everyone agreed, something altogether new and different and worth examining thoroughly.

Which is how it came to be that the doctors investigating Stephen’s case in 2014 discovered, buried deep within Hutchinson’s original observational notes on the earliest days of progeria a single inexplicable case of a man who showed every sign of rapidly advanced aging but absent all of the manifestations of progeria observed in every other case. No more was written by Hutchinson about that earliest of cases, leaving the modern doctors to conclude that Stephen’s condition in 2014 was only the second documented case of its kind in history. That it was, in fact, really two distinct observations of the same case, separated by more than a century, was a nuance that no one involved in the investigation could possibly have been equipped to realize or to comprehend. Had Hutchinson chosen to disclose Stephen’s name in his report rather than an anonymous patient number, eyebrows would surely have been raised far higher in 2014 than was already the case.

Unwilling to abandon Penny to eternity, Stephen spent his remaining days continuing his transits between the two times, though ultimately spending the great majority of his final days in the nineteenth century. Indeed, he lived long enough to witness the turn of the twentieth century, and was able to attend a New Year’s Eve party with Penny, an outing that required the assistance of an aid, Stephen’s physical condition by this time having advanced to the point of near incapacitation. The outing was a festive one, and everyone raised warm and hopeful toasts to the new century, all blissfully ignorant of the enormous economic depression and world wars that were soon to follow. Stephen died in the living room of his Bentley Street home in the late summer of 1901, lying peacefully in Penny’s loving arms, gazing in his final moments into her beautiful but grief-stricken eyes.

Less than a year later, Penny put the home and all of its sad associations up for sale, moving full-time into the coastal home the couple had long ago purchased in Camden. It was a new century, stock markets were exploding with optimism, and interest in the Bentley Street home was immediate and extensive. Less than a day after completing the listing paperwork, a young newly married couple, the husband a financier with a large bank in New York, walked through the home, thinking it a splendid place in which to spend their summers outside the city.

“Oh, Henry, look!” the wife said, entering the living room. She walked to the fireplace and stood admiring the painting. “Isn’t it lovely?” Her husband joined her and the pair stood considering the image of the house, the barn, the great spreading oak tree, and the people engaged in their various interactions upon the front lawn.

“And look at that fellow over there, the one by himself,” she said. “Whatever do you suppose that could be about?” The husband removed his glasses and leaned in to consider the figure more closely, the lone man standing adjacent the oak tree, gazing out at the viewer.

“Why, Henry,” the wife said after a moment of further examination. She turned her gaze momentarily toward her husband and then back to the painting. “Surely it’s my imagination, but that fellow looks a bit like you, don’t you think?