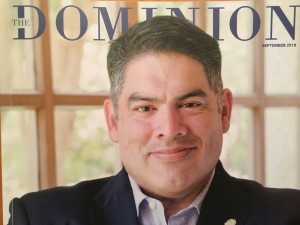

At one point in our conversation I asked Manny Pelaez to talk about the personal characteristics he believes account for the success in his legal and political career.

At one point in our conversation I asked Manny Pelaez to talk about the personal characteristics he believes account for the success in his legal and political career.

“Most guys have hobbies—fishing, football, ranch work. I enjoy reading budgets and meeting minutes.”

As unusual as that response sounds, it nicely encapsulates the complex individual who has represented the Eighth District (in which The Dominion is located) on San Antonio’s City Council since June of last year. However, understanding why this response makes sense requires a bit of context, which he was more than happy to provide during the rest of our discussion.

Manuel (Manny) Pelaez came to San Antonio in 1992, following an itinerant childhood that included being born in Chicago and spending portions of his adolescence in Tucson; Bogota, Colombia; and El Paso, the latter of which is home to The Radford School, Manny’s alma mater (his graduating class comprised just eighteen people). The stint in Colombia was part of his parents’ ceaseless commitment to a quality education, in this case to perfect their children’s Spanish skills.

Being the child of immigrant parents (Marta and Raul) is a totally different experience than that experienced by families who have lived here for generations. Manny’s parents learned to assimilate to American norms at varying paces, his mother somewhat more quickly than his father. She worked hard to rid herself of an accent, his father, a Bolivian, not so much. He describes his parents as having been “broken in” by him to life in the U.S. And while some of the events and everyday activities of American life—celebrating the fourth of July, riding a bicycle to school—took a good bit of getting used to, other events—like witnessing their first hailstorm or being driven to a medical patient’s home on a snowmobile—had more to do with living farther north than with American culture per se. But it was all new for the parents.

“My dad,” Manny recalls, “was the first Bolivian, as far as I know, to have a snowplow on the front of his truck!” That cultural difference accounts also for the lack of extracurricular activities in the Pelaez kids’ adolescent education. Manny recalls once asking about joining the school baseball team.

“If you have time for sports, then that’s more time you could be studying,” was the terse unflinching reply.

Numerous events, both within and outside of the family, were formative in the young Manny’s life. Some in particular seemed to foreshadow the political direction that his life has taken in recent years. He recalls the family driving to Lincoln, IL to take part in a visit by then President Reagan. He vividly remembers the president’s limo (the “beast”) driving by and remains convinced to this day that Reagan waved at him from inside. He was intrigued from that moment with learning what presidents actually do, and he even recalls once aspiring to the position. He spent a lot of time studying Reagan’s career, and he remembers, in particular, a trip to Washington D.C. to visit his congressman. He recalls the politician getting down on one knee and thanking the young Manny for coming to visit, exhorting him to return home and tell all his friends that he was here in the capital working for them as best he could. Manny never forgot that moment, and to this day he still feels like a little boy whenever he walks into the capital building. But his favorite president of all is LBJ, a man who got things like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 done by leveraging his influence. He remains impressed by the ability of a simple schoolteacher from the heart of Texas to rise to the highest office in the land and to use that position to try to make peoples’ lives better.

The family moved to San Antonio so that Manny could attend Trinity University, where he majored in Communications. This choice of degree caused some initial waves at the family dinner table, as all three of the Pelaez children had been raised with the express goal of becoming doctors. When Manny announced, midway through his undergraduate program, that he was going to become an attorney, the news was met with something less than enthusiasm, particularly by his father, a radiologist. Manny is the eldest of three Pelaez siblings, and in the end none of the three chose to go into medicine. His brother owns an art gallery in Austin and his sister is an attorney here in San Antonio. It should be noted that Manny did give the medical thing a fair try, taking classes in biology and chemistry. But these were not at all to his liking, as by this point he’d discovered that he had a knack for the abstract, so much so that he knew well before the halfway point of his undergraduate studies that he was headed for law school, which he promptly did immediately upon graduating form Trinity, traveling all of seven miles down the road to St. Mary’s Law School, where he found the legal curriculum every bit as rewarding as he had imagined it. By the spring of 2000 he was the proud owner of a JD degree and excited to discover what comes next.

However, at this point we need to pause for a moment and rewind. Because that announcement back in 1994—the one about NOT becoming a doctor despite his parents’ fervent wishes, the one that would take his father, in particular, so many years to wrap his head around—was by no means the only time the young Manny would raise eyebrows in the Pelaez household. In fact, two years before the shocking career announcement, within just days of starting his undergraduate program at Trinity, Manny had returned home to share the news that scarcely had he set foot on the college campus when he had met the woman he was going to marry. It’s unclear whether this was news only to his parents, or perhaps also to Diana, the future Mrs. Pelaez. But Manny had by now demonstrated a strong penchant for achieving the goals he set for himself, and starting a family would prove to be no different, though it did require, in his words, “eight years of vigorous pursuit” before the couple were finally married in 2001, shortly after his graduation from law school. And they were married right here in District Eight, at the Elizabeth Ann Seton Church, now almost seventeen years ago. Today they have two children, Max (12) and Sophia (10), the latter currently learning Mandarin, the former studying Latin and proud of his ability to name all fifty states.

Even as an adult, there have been more than a few aspects of Manny’s life in which serendipity has played a big part. One of these was his first professional position after graduation from law school. His mother Marta, a clinical psychologist, has been involved in domestic violence work for many years, including serving most recently as CEO of the San Antonio battered women’s shelter. Which is how he became legal council for the shelter immediately upon graduation (the term “volun-told” was used at one point). He remains active with this organization to the present day.

“One in four women in Texas has a domestic violence story to tell. In San Antonio it’s more like one in three. Most never make a case though, either because they’re afraid or because they don’t know how.”

We talked a good bit about what it was about the law and then politics that attracted him. He says that early on he dreamt of the law as a pathway to international legal work and a chance to travel the world. Only later, as the realities of law school began to take hold, he decided he would need to modify his expectations somewhat. He cites a quote from former president Bill Clinton: “The true test of your success in this world is whether or not the situation of the person you’re interacting with is better than when you first met.” And that, he says, has been his goal as an attorney and as a politician.

Manny’s first serious legal opportunity arose shortly after law school when he got a call from Congressman Charlie Gonzalez asking what he knew about Toyota (not much), could he speak Spanish? (yes), and was he willing to travel? (sure…where to?). Turned out Toyota was looking into starting up a new manufacturing plant in San Antonio, and they wanted their very first hire to be an attorney who could handle all the property acquisition, zoning and land use requirements, as well as the other myriad legal issues that go with starting up a large commercial facility. After eighteen months in Kentucky learning about the company and its operations, the newly minted attorney returned home and became instrumental in getting the facility up and running that today employs something like 4,000 San Antonians. It was a rapid education in the real world of corporate law, and a great opportunity to become familiar with the many politicians and organizations that make things happen in our city (a chance to “see how the sausage is made in the world of public policy”). At the same time, he learned a valuable lesson about the impact of large development projects, i.e., that not everyone emerges a winner. In the case of the Toyota project, many local homeowners were priced out of their homes because of sharp tax and valuation increases. Witnessing this aspect of the experience has made Pelaez ever sensitive to the potential downsides of economic development programs.

He was subsequently able to apply these lessons to leadership positions with Brooks City Base and VIA. On the one hand, he learned the power of government to partner with private industry to spur innovation, while at the same time remaining cognizant of the impacts these innovations can have on people living in the real world—whether that’s needing bus availability to get to a doctor’s appointment or obtaining a new job to replace the one lost as part of an unexpected base closure.

And though things have worked out splendidly for the company and the city in the years since then, Manny recalls his earliest days with Toyota, “wondering each morning if today would be the day they discover that I don’t know what I’m talking about.”

In June of last year, Pelaez was elected to the San Antonio City Council as representative of District 8, a position previously occupied by now-mayor Ron Nirenberg. Manny says that running for public office is the most difficult thing he’s ever done in his life.

“People think politics is just about kissing babies and shaking hands. But you have to get up to speed very quickly on a lot of important subjects—subjects that affect peoples’ lives. And you have to not be afraid to say from time to time ‘I don’t know,’ so long as you follow that up with ‘But I’ll find out.’”

One of his goals for serving in political office is to demonstrate to his children what leadership looks like. He regards Max and Sophia as his two primary policy consultants. “So,” I asked, “have they ever changed your mind about something? How you were going to vote on an issue?”

It didn’t take him long to come up with an example of a time when they did just that.

“I was going to vote NO on a recent issue known as ‘Tobacco 21.’ I initially felt that one more regulation for local business was a bad thing, that it would be just another obstacle to business success. Also, my sense was that San Antonio is such a porous city that underage people would simply find alternative ways to purchase tobacco products anyway, regardless of any new laws. It took my kids to remind me that smoking is a horrible practice that harms and kills thousands of people every year. If you’re selling cigarettes, you’re not doing a good thing. They changed my mind—and my vote.”

And because no conversation with the councilman on Dominion property would be complete without mentioning the Tejas Trail overhaul, we eventually made our way around to that satisfying topic.

“Within minutes of being elected last year and beginning to talk with constituents here in The Dominion, I started hearing about this horrible road called Tejas Trail. Too narrow, too overgrown, too many potholes. I finally went out and drove it for myself, and, sure enough, it was a train wreck of a road.”

So Pelaez made it his personal mission to prioritize repairs of the thoroughfare that connects The Dominion’s back gate with Camp Bullis Road. He recalls the challenge of explaining to City Manager Sheryl Sculley why such a small unknown road was worthy of a high spot on the city’s repair program. But get repaired it did, following which the new councilman visited Texas Military Institute and asked what they thought of the newly restored road.

“Somebody got it fixed!” came the enthusiastic reply. “Now our parents don’t curse so much about the road any more.”

So not only does Manny get to take credit for fixing Tejas Trail, he also enjoys being at least somewhat responsible for the significant reduction in bad language kids hear from their parents.

But what does a city councilman do in his downtime, when he’s not championing the repair of rural roads or crawling through underground sewer tunnels to make sure the city’s money is being spent wisely? Manny is an avid birdwatcher and photographer, and he has in recent months taken to constructing multi-unit birdhouses from repurposed wine crates (because what other kind of birdhouses would a fiscally-minded politician build?) He also does a bit of kayak fishing from time to time, and he is a big fan of traveling to Spain, which he has done numerous times. And because he never really completely stops working, he spends a good portion of these visits working on economic development opportunities between San Antonio and Spain, including playing an integral role in the recent visit to San Antonio of the King and Queen of Spain.

And the inevitable bucket list question? It’s mainly about the city and his family. He wants San Antonio to be the city that others look to for how things get done, whether that’s adaptive reuse of buildings, water policy, or just overall good governance. He wants the city to be known not just for The Alamo, The Riverwalk, and margueritas, but also for curing cancer and redefining how housing and traffic get managed effectively. With more than 150 people a day relocating to the Alamo City, these are goals that will serve our city well for a very long time to come.

His parents bought a house in The Dominion back in 1992, shortly after Manny entered college, and they have been here ever since. He regards The Dominion as an oasis with a sense of community that he hasn’t experienced anyplace else.

“The second you cross over the threshold it feels different. The Dominion has maintained that charm, despite being located on one of the busiest highways in the country. We have not suffered from what a lot of other gated communities have. There are plenty of events that help bring the community together. And the residents share many common values—spending time with and supporting neighbors, protecting the natural environment, etc. Having grown up here, what I miss most when I’m away is our unwavering sense of community.”

As we neared the end of our conversation, I offered the councilman an opportunity to sum up his views on where the city of San Antonio and the country are headed and how he sees his role in that future.

“There’s a strange wind blowing through American politics and civics, where rough and cold and sharp and prickly are seen as values. I find that San Antonio is filled with people who don’t see that as a sustainable model for our community in the long term. It’s what I love most about this city, and it’s the thing that’s worth fighting the hardest to protect. The character of San Antonio is why people come here. The things residents say about our city are NOT what they say about other cities. We’re at a fork in the road where we’ll either continue to grow and strive for bigger/better/faster at the expense of character, or we’ll grow but we’ll do it led and informed by character. I’m fighting for the latter.”

“Looking back at the trajectory of my life, I recall the old aphorism that eventually we all become our parents. My life is a continuation of what they started. They saw it as their responsibility to help others. I was expected to do what I’m doing now, maybe not in the doctor vs. lawyer sense, but in the far bigger sense of simply being responsible for the people around me, in whatever capacity I’m called upon to serve.”

The Dominion Magazine – September 2018