So what exactly is the story with the cardboard box full of rubber chickens? Full disclosure: I confess that I’ve wondered about this ever since the first time I visited Jazz, TX nearly two years ago and noticed the box on stage tucked discreetly beneath the baby grand piano. And though I’ve waited two years to get my answer, it didn’t occur to me to ask club owner and house bandleader Brent “Doc” Watkins this question until near the end of our conversation. But answer it he did, after a meandering discussion about how an Oregon native made his way to San Antonio and what made him want to start the area’s first true jazz club in a city known for, well, lots of other things.

So what exactly is the story with the cardboard box full of rubber chickens? Full disclosure: I confess that I’ve wondered about this ever since the first time I visited Jazz, TX nearly two years ago and noticed the box on stage tucked discreetly beneath the baby grand piano. And though I’ve waited two years to get my answer, it didn’t occur to me to ask club owner and house bandleader Brent “Doc” Watkins this question until near the end of our conversation. But answer it he did, after a meandering discussion about how an Oregon native made his way to San Antonio and what made him want to start the area’s first true jazz club in a city known for, well, lots of other things.

Doc Watkins hails originally from the Portland, Oregon area. When his mother remarried he was just two and the young family relocated for several years to San Diego. But then, around the time Doc was turning ten, he, his mother, stepfather, and six stepsiblings all moved back to Oregon.

“I’m the oldest of all the kids. It was definitely a full household, with never a dull moment. We had lots of land around the house. There were pear and apple orchards, strawberry fields, blackberry bushes. We had a lot of room to roam and get into trouble.”

The young Doc was into sports as a child, in particular football and baseball. But he also played music from a very young age, and it was ultimately that path that he would pursue.

“I was into music from a very young age, perhaps in part because my father had worked as a musician. Even though we all took piano lessons growing up, I’m the only one who’s a musician today. You really can’t escape those early formative years.”

Around age five, Doc asked his parents for a piano, and they obliged, finding an old upright model for $300. The family was still living in San Diego when he began taking lessons. He recalls picking up music very quickly, both sight-reading and playing by ear. So astute was his natural musical sense that his instructor would bring in other teachers to watch as the young student called out individual notes simply by hearing them played.

“I was such a ham in school. I would play for fellow students and compete in talent shows as a way to get attention. I remember wearing out cassette tapes playing them over and over, trying to pick out individual notes and chords.”

But the young Doc hadn’t given much thought to what he would do after high school.

“When you’re a sixteen-year-old kid and you really like playing the piano, you’re not thinking about a plan for when you’re going to be thirty. All I knew was that I wanted to play music. In fact, when I graduated from high school, I had a scholarship from Southern Oregon University to play football and to pursue music. But I decided there weren’t enough hours in the day to do both, so I opted for music, since that was my first love. Also it was pretty evident I didn’t have the athletic talent to make a living playing professional sports.”

At Southern Oregon, Doc studied under pianist Alexander Tutunov, pursuing classical training in what he imagined would be a straightforward path to a musical career. But things didn’t quite work out according to plan.

“Many colleges will tell entering students that there are a lot of music jobs out there. But college professors more often than not are simply teaching other people to become professors. I was probably a bit gullible at that stage of my life. I loved working with Alexander, but I wasn’t thinking as much as I should have been about what I was going to do after college. As I neared graduation, only then did my professors tell me that I couldn’t expect to have a career with just an undergraduate music degree. Naturally they encouraged me to go to grad school. So I toured Julliard, Eastman, etc., but I really liked UT Austin, and I figured I’d go there and just do a Masters. However, though it wasn’t explicitly stated, it was certainly implied that the progression was to go all the way to a Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) and to then look for a tenure-track teaching position.”

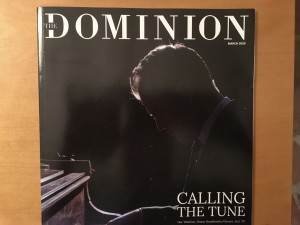

It was during his time at UT that the “Doc” nickname took hold, one that he’s embraced ever since. The other thing that took hold during his time in Austin was a love of all things Texan. He had originally come to study under pianist Gregory Allen, and while the majority of that formal instruction was in classical music, Doc had, for a long time, felt a somewhat different calling, one that led him to sneak into the occasional jazz class, exhorting others in the class not to tell anyone lest the classical faculty learn of his defection.

And how did Doc’s formal music education inform who he is today?

“In all honesty, I likely could have stopped school five years earlier and been fine doing what I’m doing now. Still, exploring the greatest musical works of all time with a mentor—there’s no substitute for that. But all those papers and lectures were, frankly, nothing but a headache. Working with Gregory was great. He didn’t care much about competitions or school politics or bureaucracy. He was just there to make me play the very best that I could. It’s very much a master/apprentice relationship—like Yoda and Luke Skywalker!

“But there’s a big difference between loving classical music and loving the environment in which classical music lives. I adore the music to this day, but I have no tolerance for the closed-mindedness and arrogance that attend the highly educated classical audience. I’m not in it to demonstrate how perfectly I can play a piece or to have listeners count how many notes I miss. That’s why I’ve never been a fan of competitions.”

With his newly minted doctoral degree, Doc accepted a faculty position at UTSA. But that only lasted a year because the entire time he kept coming back to the realization that all he really wanted to do was perform music. Surprisingly, perhaps, for a musician, Doc couldn’t wait to get out of Austin and down to San Antonio. In Austin he felt as though the musicians tended to think alike, that there was a bit of a herd mentality.

“You take twenty musicians and put them together, and eventually they start to sound the same. It’s easy to lose the sense of your own identity. Mark Twain once said ‘There are only four unique cities in America: Boston, New Orleans, San Francisco, and San Antonio,’ and I think he was right, about San Antonio at least. I love it here because there’s room to do what I want to do. Every musician copies others early in their career. But at some point you have to find your own voice. Ray Charles sounded like Nat King Cole in his early recordings, until an agent told him that the world didn’t need another Nat King Cole.”

And was there one particular moment when Doc realized that jazz was the path his life would take?

“I was watching a YouTube video of Billy Preston and it struck me that what I was watching was pure joy. That was a seminal/transitional moment for me. I didn’t want to have to justify why I loved it; I just loved it. I decided then and there I was going to make my life no more complicated than simply doing what I truly get joy from doing.”

And so Doc went out and started his first band, teaching himself jazz along the way. While learning the standards of Gerschwin, Porter, and others, he also discovered that he really enjoyed being a bandleader.

“I love playing with a group. There’s a certain light-heartedness and camaraderie that’s hard to capture as a solo performer. When you’re a solo pianist, it’s just you. You can be the best quarterback in football history, but if you’re on the wrong team, you’re not going to be successful. I like the familiarity of it. As for the leadership thing, I always felt that I could do a better job than most of the other bandleaders I was working with. I guess I just didn’t care much for the songs they were calling, and I figured that if I was leading, I could choose the songs that I liked.”

As a bandleader, Doc’s band quickly gained a reputation and picked up a lot of work. All the clubs and restaurants in town wanted to hire them, with things eventually getting to a point where they were doing multiple gigs a day.

“People would ask if we were available and oftentimes I’d have to say no. But it occurred to me that I could maybe start my own booking agency because there was so much demand in town for other bands. There were nights when I would have as many as fifty jazz musicians working in San Antonio. I was creating work for other people and was able to make a living doing it. By doing booking and having the only agency of its kind in the city, a natural relationship started to develop with the Pearl and its leaders. I started talking with folks like Craig Wilson, Elizabeth Fauerso, and architect Jonathan Carr about what would it look like to start a club.”

Jazz, TX is located in the basement beneath the Food Hall at the Pearl. And though the building looks antique, it’s actually relatively new construction, with the old bottling department building having burnt in 2004. The original plan for the new structure did not include a basement, but after detailed discussions with Doc about what he felt he would need for a successful jazz club, the builders agreed to include the basement. Now, five years on, Doc and his band play two hundred shows a year at the club in addition to the gigs he does in other venues around the country.

“We’ve played all over, from Carnegie Hall to Reading, California. We particularly enjoy going where people have never heard a jazz band before. It’s hard to predict what people are going to like. Sometimes you only know when you play and you see what sort of reaction you get.”

And how does he feel about his music these days, particularly since he has to share his love of performance with the more mundane duties of keeping a business running?

“The business part of it has always been challenging since I had virtually no experience coming into this endeavor. Flexibility is a good thing though. My band members and I even ended up building some of the club. One of our contractors wasn’t doing as good a job as we wanted and so the guys and I just brought our tools one day and started building the stage and some of the other structures. I’ve probably risked doing damage to my hands more with a utility knife here at the club than anything else I do.

“As for the music, no matter how hard I try, I can’t get away from the classical influence. I can’t not approach the piano like a classical musician. The jazz part has less to do with traditional jazz and more to do with gospel, R&B, that sort of thing. Heck, I’ve even busted out a classical piece in the midst of a jazz show—some Chopin, Brahms, or maybe Bach—people love it. And, of course, I’ve tried some things that completely fell down. But you have to keep pushing yourself, taking risks.”

What is family life like for a working musician with a spouse and four kids?

“Jessica works with me here at the club, helping out with social media and business planning. She’s a musician too (violin), so she understands the passion that goes into it. We’ve known each other since we were kids back in Oregon, so we definitely get each other. My kids probably have a better intuition about music than most, since they’re around it all the time. After all, we’re frequently practicing and sometimes even recording in our living room at home.”

Having accomplished so much to this point in his life, what comes next?

“I honestly have no ideas about the future. At pretty much any point in my life, I had no idea what was waiting five years down the road. Best you can do is to set personal goals, then be open to putting them aside if something unexpected comes up. Too often we underestimate the influence of completely unforeseen events in our lives. Life can turn on a dime with one conversation or event. I’ve found that almost all of the shifts in my life have come about because of unforeseen one-off situations. If I hadn’t gone to that party, met this person, returned an email, I might still be in Oregon.”

And so, at long last, we come to it. What is the deal with the rubber chickens? And what on earth do they have to do with a club that’s dedicated to the creation of great music and giving audiences a fun time?

“So, when I started the club, I got into the habit of talking with the audience at various points in the show, just joking around. I’ve always loved stand-up comedy. I grew up listening to Steve Martin and other well-known comedians. I’d try to open up each show with three or four minutes of stand-up comedy. I’m always amazed at people who can do that—you on stage with nothing but a microphone, nothing to hide behind. I’ve thought at various points in my life that I’d like to give that a try, but I just keep chickening out. So, I thought, what if we had some props? I liked the look of rubber chickens. So for the last three years we’ve been trying to somehow work rubber chickens into the show. But with perfect consistency, they never get a laugh. And that has become the joke. Unlike music, which you can practice and practice until you get it perfect, with comedy it doesn’t matter how funny you think something is until you do it in front of a live audience. Sometimes now we give an audience member a rubber chicken as a gift. Usually the audience just looks at me and wonders what’s that all about? Someday maybe I’ll actually get a laugh. Maybe.”

So how do you summarize a life spent pursuing the fine art of entertaining an audience?

“ I keep coming back to the same idea, which is that it’s all about the people. What I enjoy most is bringing people together through music—showing them a good time and making them happy. Nothing is more fun than watching an audience that’s having a good time. For me that’s a lot more important than feeling like I have to impress them, and certainly more important than winning awards. That’s what motivated me to create my own music venue in the first place. I just wanted to realize that vision. When you play concert halls, you don’t know who your audience is, but being able to have our own venue and to create an environment where folks have a great time is what makes it all work.”