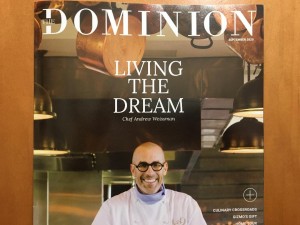

“Throughout my business career, I’ve always planned for a rainy day,” says Chef Andrew Weissman, almost certainly San Antonio’s best-known practitioner of the culinary arts. “I just never imagined that all the rain would fall on the same day”

“Throughout my business career, I’ve always planned for a rainy day,” says Chef Andrew Weissman, almost certainly San Antonio’s best-known practitioner of the culinary arts. “I just never imagined that all the rain would fall on the same day”

Our conversation—which takes place in the otherwise empty dining room of Signature restaurant—went almost immediately to the coronavirus pandemic and its likely impact on the restaurant community, both here in San Antonio and nationwide.

“Things are going to be drastically different,” Weissman continues. “Almost like a massive forest fire that burns down the old trees to promote new growth. I think restaurants that were teetering on the edge are going to get swept away. With that there will be lots of mom and pop operations that don’t make it. It just seems to get worse with every passing day. I think there will be fewer restaurants, but the ones that survive will be way more efficient and will pivot to offering new ways for customers to dine out.”

Chef Weissman is a restaurateur par excellence, owner of nine past and current establishments in San Antonio, including most notably Le Rêve, the Alamo City’s first serious foray into fine French dining (opened in 1996, closed in 2007); Il Sogno Osteria, the fine Italian restaurant that served as one of the catalysts for the renovation of The Pearl from 2009 to 2018; and Weissman’s latest culinary love letter to his home city, Signature, opened in 2016 at the La Cantera Resort and Spa. But why, one might reasonably ask, close down a restaurant that’s doing spectacularly well (with a three-month waiting list in the case of Le Rêve)? It’s a complicated question, one we’ll come back to later in this story.

Weissman is a San Antonio native who grew up in the northern part of the city with his brother and two sisters, all of whom attended Churchill High School. His parents divorced when he was seventeen, and he recalls his mother always being the strong one in the family.

“For as long as I can remember, she’s been a very creative individual. She ran a gift and tchotchke shop in Olmos Park for years called “What’s in a Name” while also raising the four of us by herself. I’m frankly kind of amazed that she was able to pull that off. She’s still around and as active as ever at eighty.”

As a youth, Andrew spent a great deal of time outside, playing with friends, searching for snakes under old boards, typical young boy stuff. The first thing he recalls being passionate about was drawing.

“Going into high school, I didn’t really think I was a standout at anything, although I enjoyed drawing. The cooking idea hadn’t begun to blossom yet, but I did have a habit of making nachos for my friends when they would come to the house.”

He acknowledges that food was an important part of his upbringing. His mother was a member of a gourmet group that met once a month and shared dishes from various areas of the world. It’s a group that started around the time her oldest son was twelve, one that continues to this day.

Weissman’s original career path—one that didn’t last long, to San Antonio’s great benefit—was journalism. He graduated from the University of North Texas with a degree in radio, television, and film, and a minor in journalism, deciding immediately thereafter that he would move to Mexico City.

“I knew Bob Rivard at the time, and he got me connected with Carmen Danini in Mexico City. That, in turn, enabled me to set up a meeting with the bureau chief of NBC News in Polanco near Mexico City. So I went to the meeting and the bureau chief agreed to let me stay there and write if I wanted. I had traveled to Mexico with friends a lot growing up, and I loved the food and the culture. I figured why don’t I try to sell stories about Mexico that are relevant to Texas? I’d tag along with the staff photographer and try to get him to let me do stand-up reports. Turned out I really hated being in front of the camera. I think I sold maybe two stories my whole time there.”

At this point in the young would-be journalist’s career, serendipity entered the picture in the person of NBC White House correspondent George Lewis. The world-renowned reporter was in Mexico City to do a story on the Mexican president. To this point, Weissman had been preparing meals for the other staff members at the bureau, and the bureau chief suggested that he prepare something for everybody when Lewis came to the office with his crew.

“I was just happy they were willing to let me hang around the office. I’d go to the mercado from time to time, buy a few ingredients, and make meals for everyone. The day I cooked for Lewis and his team, he told me it was the best meal he’d ever had. I mustered all my nerve and told him that I aspired to have his job. ‘No you don’t,’ Lewis responded to me. ‘I never see my wife and kids. You should go to cooking school.’”

The next day, Andrew was on the phone to his mother telling her that he wanted to apply to culinary school. As luck would have it, he was dating a girl at the time who had a friend attending The Culinary Institute of America (CIA) at its main campus in Hyde Park, New York. She offered to connect the two and to get more information on the school.

“At the time, I wasn’t even aware that culinary school was a thing. Once I got back to San Antonio, I made a few calls and soon I had a VHS tape all about the school. I was totally blown away by the campus. I asked a few chefs in San Antonio what was the best culinary school, and they all said CIA. So I decided to give it a go.”

Weissman has received more than his share of breaks in his professional career, and his initial interaction with the CIA was his first big one (arguably a tie for first place with his George Lewis encounter). It’s relatively uncommon for students to apply after having already completed a bachelor’s degree elsewhere, and so the school made every effort to attract the young Texan. They offered him a $1200 scholarship if he could get to the school in just a week to start the summer semester.

“They wanted a couple of recommendations and at least six months of industry experience in order to apply. Fortunately I had, by that point, already been working for Mike Bomberg at Anaqua Grill for a couple of months. So that, combined with a couple of dishwashing jobs I’d had, met the requirement. I headed to New York with little more than my duffel bag.”

Another break that the young aspiring chef got around this time was that the girl he was dating got an offer to attend the University of Hartford. On weekends, the couple would visit restaurants all over the northeast, which led to Andrew landing a position at The Homestead Inn in Belle Haven, Connecticut, working under Chef Jacques Thibaud.

“Chef Jacques really took me under his wing. Pretty much the entire kitchen was staffed with French and Moroccans. I was the only American kid. During the summer between years at CIA I did my externship full-time at the restaurant and even lived there on the premises. That’s how I became acquainted with Marc Sarrazin.”

Ask any French chef who came to America in the eighties and nineties how they got here, and at some point Marc Sarrazin’s name is likely to come up. He was an extremely influential meatpacker who was instrumental in bringing many of the best-known chefs to this country, with the quid pro quo being that they agree to purchase all of their meats from his company. Unbeknownst to the young Weissman, his mentor Jacques Thibaud was one such chef. And so it came as a surprise to learn toward the end of his time at the CIA that Sarrazin had been monitoring his career throughout his time at Hyde Park, and even more of a surprise when he was asked to go to the CIA president’s office. It was at that meeting—attended by the top five students in Weissman’s class, of which Andrew was one—that Sarrazin not only offered to pay all of the students’ education costs, but to also set each of them up in whatever post-graduation situation they wanted. It wasn’t something Weissman had thought much about to this point, but when prompted about his post-graduate goals, he responded that he would like to refine his cooking skills in France.

“It’s done,” Sarrazin said. And that was that. A few weeks later Weissman found himself in Burgundy working as stagier. He would go on to spend a year in several of France’s finest restaurants. Following that year, Thibaud again approached Weissman to let him know that the famed New York eatery Le Cirque was being reopened in a new facility and that Weissman should apply for one of the coveted positions.

“It was unbelievably competitive and cutthroat,” Weissman recalls. “And it was nonstop celebrities—politicians, actors, you name it. If they were anybody, they were eating at Le Cirque. I remember Chuck Mangione sitting in the kitchen and playing trumpet while we cooked. It was all kind of surreal. But the schedule was brutal—7 a.m. to midnight seven days a week. And the owner constantly threatened anyone who complained. All he had to do was wave around his massive stack of resumes of others who wanted to work there. But it was so cutthroat; people would go behind you and break your knife tip off or sabotage your dish. Crazy stuff.”

After a year or so in the heady atmosphere of New York’s most famous restaurant, Weissman began searching for opportunities elsewhere, with the original goal of finding another renowned restaurant. But first, he decided to pay a visit home, something he hadn’t done in some years.

“The original plan was to go home for ten days and then rejoin the job search. Only then my sister took me out to look at a tiny restaurant that had just gone out of business. I remember peering in the window, knocking on the glass, and eventually speaking with a cleaning person inside, asking if the space was for lease. He gave me the property owner’s number and the next day we spoke. That was the site that became Le Rêve.”

Fast forward a few months and forty thousand dollars cobbled together from a small group of friends and family members, and La Rêve was opened to rave reviews.

“I came back to San Antonio with no money. The owners at Le Cirque had paid very little, feeling that, in fact, we should be paying them for the privilege of working there. Combine that with the New York City cost of living, and it wasn’t exactly a recipe for having much of a savings account. So I bought lots of used equipment and put the whole thing together myself.”

It would prove to be an intense but ultimately unsustainable lifestyle. The restaurant received nothing but accolades and enjoyed a three-month waiting list, partly because of its excellence and partly because there was simply nothing else like it in San Antonio.

“We would work like dogs every day and then spend each August in France. It’s a very physical style of cooking and it really takes it out of you after a while. But we stuck with it for a decade or so, until one day around 2007, I got a call from Kit Goldsbury, owner of the Pearl Brewery, wanting to know if I would consider opening what would become the first restaurant in the newly renovated Pearl.”

Which is how Il Sogno Osteria came to be. (Side note: Il Sogno and Le Rêve bothmean The Dream, in Italian and French respectively. When quizzed about those name choices, Weissman’s response makes perfect sense—“It had always been my dream to open an amazing restaurant.”). Il Sogno would go on to collect reviews and accolades on par with those from Le Rêve until the former was finally closed in 2018 (much to the chagrin of this writer and many others in San Antonio).

Along the way, Weissman would also open, and have enormous success with, The Sandbar Fish House and Market (modeled on an east coast oyster bar), Moshe’s Golden Falafel, Sip Brew Bar and Eatery (a coffee lover’s coffee bar), The Luxury (built near the Riverwalk using repurposed shipping containers), Mr. Juicy Burgers (Weissman’s first foray into fast food), and, most recently, Signature at La Cantera Resort. So, we asked a question back at the start of the story: Why close down something that’s in the midst of being wildly successful? I asserted that the answer to the question was complicated, and by now it should be pretty clear whence those complications arise.

First and foremost, Andrew Weissman is a genuine hands-on guy. Call it being a control freak if you like, but he is extremely dedicated to ensuring that everything that comes out of any of his kitchens is as close to perfect as can be achieved. And that means he’s not the sort of individual to open a restaurant and then trust its operation to a manager who he only sees once or twice a week, a model commonly practiced by other restaurateurs. Add to this personality trait a strong sense of family commitment, a desire to NOT spend every waking hour of every day working, and throw in a dash of desire to constantly be experimenting with new cuisines and new business models, and that’s how you end up with tremendously successful establishments like Le Rêve and Il Sogno being closed after a decade or so of wildly successful operation. Any chance he might just have a short attention span, I ventured? He concedes the point, admitting that he’s always looking for ways to expand his knowledge about both cuisine and business, and that he personally gets more energy out of starting things than out of running them once they’re going. At the moment he is primarily focused on Signature (its current COVID-19 closure notwithstanding), but is also making ambitious plans for expanding Mr. Juicy into a much larger chain, perhaps as many as thirty locations, he says.

“I’m really trying to build the Mr. Juicy brand. But at the same time, I’ve been very hands-on at Signature since it first opened four years ago. The product here has been exceptional. It’s very experiential, with diners routinely spending two or three hours over dinner. Yeah, I’m a perfectionist, but I think it’s served me pretty well. Every restaurant I’ve sold or closed has been on my terms, and each has been very profitable.”

Andrew’s wife, Maureen, hails from Costa Rica, a country the family briefly moved to a couple of years ago before professional demands brought them back to Texas. The couple met while Andrew was running Le Rêve, through the matchmaking efforts of his restaurant valet, and they have been married eighteen years in August with three children—8, 12, and 13.

“I realized along the way that it’s all about the family. I’ve been blessed in thousands of ways, especially in that I found early on what I was meant to do. It’s freeing in a way to know that I can do this anywhere. If it doesn’t work in San Antonio, I can always go back to Europe. And even if I lose everything, I still have my family. It’s a no-lose type of deal.”

While discussing family, a curious memory is triggered.

“We were in the south of France once on the beach and I watched this man working a grill while his son dove into the water and pulled out fish. The father than took the fish, cleaned them, cooked them, and served them to the beachgoers right on the spot. I remember thinking: I could do that. Except, because I’m an entrepreneur, I’d probably get my wife to photograph each experience and sell the pictures along with the meal.”

That’s the sort of vision you get from a guy who’s always thinking about taking dining to another level and another experience.