Every metal has its melting point. But for even the most malleable of alloys, that point is far higher than the flash point of paper, fabric, or human flesh.

Every metal has its melting point. But for even the most malleable of alloys, that point is far higher than the flash point of paper, fabric, or human flesh.

This happy thought springs to mind as my tiny Mercury space capsule, code-named ‘Annabelle 1’, hurtles toward the sun at nearly forty times the speed of sound. Well, not exactly towards it, but in an inescapably declining orbit whose destination is, nonetheless, that most sweltering of destinations.

It’s been twelve hours since the capsule’s retrorocket system failed – twelve hours. Hell, by now I should be aboard the carrier – cleaned up, sipping champagne, and on my way home. Instead, the engines failed to slow my momentum enough to allow reentry into earth’s atmosphere.

God knows, the original mission plan was simple enough – orbit earth for three days, then descend to the Pacific Ocean gently and triumphantly beneath a pair of bright orange parachutes, into the waiting arms of an adoring public. I might have even gotten to visit the White House. Annabelle would have loved that – see the White House, meet the President and first lady. That’s the sort of thing a kid never forgets. Still, based on how this is all shaping up, she’ll probably get to meet them anyway, if only to accept my posthumous medal.

Actually, the three-day part of the mission went precisely as planned. I made it through all the scheduled experiments, even managed to demonstrate that you could maneuver and control this tin can of a spacecraft. It’s only our third foray into space – low earth orbit to be specific – and, frankly, the brass weren’t expecting much of me other than to survive and not break anything.

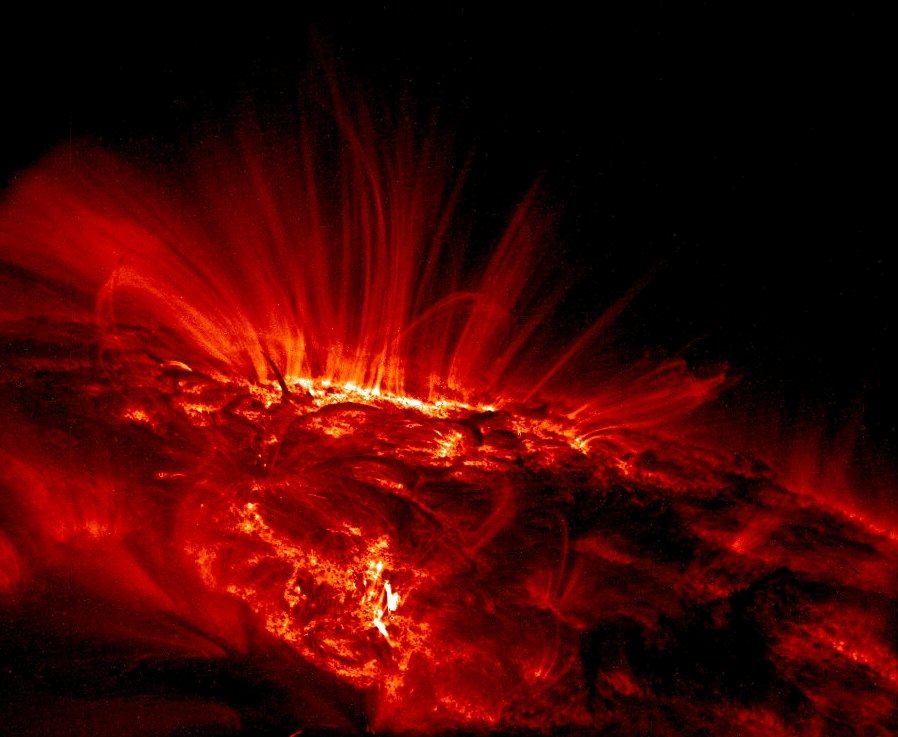

But now, despite my best efforts, it looks as though I’ll fail at both of these basic objectives. Instead of braking and descending, the capsule caromed off the outer layer of the atmosphere like a flat stone on a still pond. It then promptly departed earth orbit and is now on a new trajectory that Mission Control says is steeply declining. In six days I’ll be close enough to the sun for the capsule to build up an external skin temperature of one thousand degrees Fahrenheit. The good news is that NASA has provided me with an ample supply of oxygen to last until the “conclusion” of my mission. The ground controllers deliver this news in their usual professional, even-toned manner, and then the radio goes silent as my antenna succumbs to sunspot interference. Looks as though I‘m alone for the remainder of the journey.

As the distant voice on the speaker fades to white noise, my gaze falls upon a small photograph taped to one of the instrument panel’s few blank spots. Annabelle grins back at me, her five-year-old green eyes big and round like a new puppy, and her smile all lips and no teeth – she doesn’t like showing her braces.

“Will you be back in time for my play on Saturday night?” was her last question before I left the house that morning.

“I’ll be there if I have to climb out of my spaceship and float down on a bunch of balloons,” I promised her. Saturday night – one week from now. It will be a strange thing, I guess. The play will go on; no one will much miss me. Annabelle will wonder why I didn’t come – why I broke my promise. She’ll be disappointed, but she’ll go on nevertheless. Your family gets used to that sort of thing when you’re in the military. There are lots of times you don’t make it home…I just hope they don’t tell her anything until after the play.

Jenny and Ron will be good parents. They knew this day could come. They understood that the godparenting thing was a little more serious commitment than normal in my line of work. A real pity she can’t be with her mom. Matter of fact, looks now like I’ll be seeing mom before anyone else. Damn it – I hate breaking promises to that kid. What an angel…a cream-skinned, puppy-eyed angel.

All right, let’s focus – weigh our options, such as they are. Annoyingly enough, I can envision no scenarios that involve my setting foot on earth (or any other planet) again. Every variation of this story ends the same. So I guess it remains only to dream up a plan that makes this inescapable outcome as tolerable as possible.

A key consideration would seem to be speed of action. Do I accelerate the inevitable, or delay things as long as possible? Choosing the latter requires only that I sit back, breathe slowly, and wait for events to unfold on their own. The engines are useless, and I have no control over the capsule’s trajectory. If, on the other hand, I want to move things along as quickly as possible, I could just blow the hatch, and that, as they say, would be that. Alternatively, I could achieve the same result by simply venting all my remaining oxygen into space. That would leave me to suffocate in relatively short order.

Freeze, suffocate, roast – there must be other alternatives I’m overlooking. Maybe I can find some sharp metal object inside the capsule and cut my throat. It’s worth considering, but I’m not sure I’m capable of that degree of active violence, even under the circumstances. As I ponder the creative opportunity unfolding before me, one thing is clear – I’m in no danger of dying from hunger or thirst. Either of these requires far more time than the other alternatives on my growing list. Curiously, there’s a mild sense of relief in having reached at least one definitive conclusion from all of this. May as well go out on a full stomach – I tear open a small food tube and hungrily consume the tasteless paste while continuing to think about additional possibilities. As I cogitate, my slowly tumbling capsule periodically aligns itself so that the sun’s rays briefly flood in through the small window above my head. It’s like a slowly swinging pendulum, ticking away the remaining hours of life. No…more like being on death row and getting a phone call from the executioner every ten minutes or so.

So, let’s review one more time, we’ve got bleeding to death, suffocating, freezing, and roasting, in more or less descending order of attractiveness. I wonder if maybe I could knock myself unconscious. Doubtful; it’s pretty tight in here. It’d be damned tough achieving the necessary momentum to pull off such a thing. Don’t the Russians give their cosmonauts cyanide pills for occasions like this? Just my luck – working for an organization with the hubris of NASA. Still, there must be other creative alternatives. Feeling a strange and morbid fascination at the idea, it suddenly occurs to me that the list of options is becoming long enough so that maybe I ought to write it down. Now there’s an artifact for our fledgling space program – pity no one will ever find it.

As I begin to exhaust the possible solutions to my “dilemma”, several more far-fetched notions cross my mind. Can I create some sort of chemical reaction on board that will cause an explosion? How about diverting a toxic chemical into the cockpit and poisoning myself? NASA, I realize with still more annoyance, has taken great pains to engineer the capsule against any such malfunctions. Is it feasible, I suddenly wonder, with a pitiful glimpse of hope, to put on my helmet and attempt a space walk to repair the engines? Useless on two counts, I immediately conclude. First, there is no provision for oxygen in my suit, meaning that even if a repair were possible, I’d would have to complete it in less than a minute or two. More to the point, even if I pulled off such a miracle, perfectly functional engines could, at this point, achieve nothing more than propelling me into a different region of space.

Nearly sixteen hours now since the failed reentry, most of which I’ve spent debating with myself the optimal means of self-destruction. Following close on three solid days of science experiments and capsule maneuvering, I now slowly succumb to exhaustion, and drift into a nervous sleep, punctuated by the incessant noises and lights that continue to emanate from the capsule, despite its mostly inert state.

Asleep now and dreaming of a beautiful little girl with her mother’s strawberry blonde hair, a small red ranch house in the country, rolling meadows blanketed with dandelions, frolicking golden retrievers, fireflies in a jar. And then more dreams – a titanium capsule glowing cherry red, funeral services, repetitious news stories, a baby girl’s delivery gone bad.

Strange sensations now as I slowly wake from a deep sleep. I’m confused for a moment, hearing what sounds for all the world like the roar of a jet engine. This is, of course, impossible, since my capsule’s propulsion system ceased to function long ago. Perhaps I’m exhibiting the first signs of madness one might reasonably expect of a doomed astronaut. As I rub my eyes my vision blurs briefly, then slowly begins to sharpen. But the scene that materializes before me is not the capsule’s instrument panel, with its dull gray paint and clutter of gauges, lights, and switches. Rather, I am staring straight up at the unmistakable deep azure sky of the South Pacific. Well there you go; I’ve already died somehow, and here I am in heaven – or wherever. It is a reasonable and not unattractive possibility, but one immediately obviated by what appears to be a Navy medical officer now leaning into my field of vision.

“Colonel…Colonel…can you hear me?” the officer’s voice seems somehow distant from his moving lips.

Turning my head first to one side, then the other, I can see numerous Navy and NASA personnel, some clad in bright orange flight suits, others in dull military green. Lifting my head slightly, I see the white and gray fuselage of an HSS-2 rescue helicopter. And sitting on the deck next to the chopper, tilted awkwardly to one side, the charred but intact capsule in which I’ve spent the past three days, its partially deflated flotation collar still attached.

“I think he’s coming around, sir.” the medical officer says, turning to the ship’s captain. “Colonel,” he says again, turning back to where I remain prostrate on the deck of the carrier. “I’m Lieutenant Commander Billings. Do you know where you are?”

I utter something of dubious intelligibility, and they quickly infer from my babbling and glazed expression that not only do I not know where I am, but probably not even what day it is.

“You’re on the Intrepid, sir,” the officer continues, “and you’re fine, at least so far as we can tell. You hit pretty hard though – one of your chutes got tangled, and your capsule hit the water at about eighty knots. That’s a bit faster than she was designed for, sir, but the flotation collar still worked fine. You took a pretty good knock though, and you’ve been out for ten minutes or so – not bad, all things considered.”

I slowly sit up on the deck and continue looking around – first at the nearby medics and crewmembers, then the helicopter, and finally the capsule with its blackened bottom, high-visibility-red flotation collar, and open hatch. The hand-painted letters ‘Annabelle 1’ are barely visible through the soot that coats the capsule.

“Can you stand, sir, or should we stretcher you into the infirmary?” the officer asks.

So I made it – son of a bitch. No ride into the sun this time. I wobble a bit and rise to my feet with the help of a couple crewmen. There is no way the third American man in space is being carried across the deck of this ship. As I stand, I still feel pretty wobbly, and I put a hand to the side of my head as a sudden blood rush briefly overtakes me.

“Take it slow, sir. We’ve got all day,” says the ship’s captain. “Ensign, give the Colonel a hand” he adds, motioning to one of his aides.

I begin making my way across the carrier deck, with diminishing need for assistance, and the sailors and NASA staff on board began a slow rhythmic applause that increases in frequency and vigor, reaching a crescendo as I approach the oval door in the side of the ship’s island. I pause before stepping through the doorway, turning to wave enthusiastically to the ship’s crew.

After a few minutes navigating the confusing steel corridors of the ship’s lower decks, my entourage and I reach the ship’s infirmary.

“Now that you’re among the living again” the medical officer says, “you have several hours of post-flight medical checks to look forward to. Fortunately, we will be four days steaming back to Pearl, so there’s plenty of time. My first professional recommendation is that you receive a mild sedative and enjoy a couple of hours in the prone position.”

I am in no state of mind to disagree, and I sit down heavily on one of the infirmary’s white linen covered cots. I doubt that I need a sedative, but nonetheless hold up my left arm for the medical corpsman as he approaches with a small hypodermic.

“We’ll give you a couple of hours” the officer says with a smile, “then get you a decent meal – one that doesn’t involve squeezing any tubes. Once you’re back to a hundred percent, we can start all the poking and prodding. I’ll see you in a little while.”

He walks quickly out of the infirmary, with the rest of the medical team close behind. The last man out shuts off the lights and pulls the door to as I settle back onto the crisp sheets, still wondering at the mission’s success and the prospect of being home in a few days. I find myself imagining what Annabelle will be wearing in the school play. Eighty knots, I think, drifting off. That must have been one hell of a splash….

Two hours pass. Maybe three. But it seems I’ve barely laid my head back when my sleep is interrupted by a steady beeping sound, and a faint red light that appears directly in my field of vision, flashing in time to the sound. The infirmary room is very dark and, still groggy from the sedative, I hesitate before attempting to sit up. What sort of medical apparatus have they got me connected to anyway? Probably just a heart monitor to ensure their investment is still in working order. My thoughts clearer now, I lift my head from the pillow.

I lean upward only a foot or so in the darkness and my forehead connects suddenly and painfully with some heavy metal obstacle. Falling back, I curse and pause again, straining, forcing my eyes to refocus on the blinking light in front of me. But as I stare, the light grows slowly steadily fainter and the beeping sound that awakened me diminishes in intensity. Leaning forward once more, this time more cautiously, I am now fully awake and can clearly make out the tiny “Critical Battery Level” label immediately below the flashing light. I stare incredulous into the light as it continues flashing, perhaps a dozen more pulses before fading out one final time. The beeping noise continues for another minute or so before it too subsides, leaving me alone in the silence of my now powerless capsule.

The situation comes into stark clarity in my mind, and I slowly turn my head upward to gaze out of the capsule window. As my face rises, the slowly rotating capsule again aligns itself so that a flood of light from the now enormous sun streams into the cockpit. Looking away from the window to avoid the star’s brilliance, my gaze settles for just a moment on Annabelle’s photo, and then I look down at the small notepad attached to the wrist of my spacesuit. Squinting, I focus on the pad and what appears to be a short handwritten checklist. Thinking one more time about the carrier, the infirmary, the school play, and a broken promise, I slowly read down the list – bleeding, suffocating, freezing, roasting…