A dense cloud of highly radioactive steam billowed and swirled around the broken reactor pipefitting. The technicians before the control room’s large monitor struggled to see through the cloud, occasionally catching glimpses of the labyrinthine mass of stainless steel tubing surrounding the main vessel. The observers could also clearly hear over the intercom the piercing hiss of steam being forced out under high pressure from the fractured valve joint. The control room foreman turned for a quick glance at the radioactivity gauge in the center of the Vessel 3 control instrument cluster – thirty seven thousand rems, more than one hundred times the fatal short-term dosage for a human. As he turned back to the monitor screen, the hissing sound gradually faded out and was replaced by the steady thrumming of turbine pumps.

A dense cloud of highly radioactive steam billowed and swirled around the broken reactor pipefitting. The technicians before the control room’s large monitor struggled to see through the cloud, occasionally catching glimpses of the labyrinthine mass of stainless steel tubing surrounding the main vessel. The observers could also clearly hear over the intercom the piercing hiss of steam being forced out under high pressure from the fractured valve joint. The control room foreman turned for a quick glance at the radioactivity gauge in the center of the Vessel 3 control instrument cluster – thirty seven thousand rems, more than one hundred times the fatal short-term dosage for a human. As he turned back to the monitor screen, the hissing sound gradually faded out and was replaced by the steady thrumming of turbine pumps.

“That ought to just about do it,” came a hollow-sounding voice over the speakers. “Your steam pressure should be coming back up any second.”

With the leak stopped and the ventilation fans recirculating more than five thousand cubic feet of air in the reactor containment area per second, the air quickly cleared, revealing two men wearing tool belts and clothed in nothing but jeans and long-sleeved dress shirts.

“Looks good out here,” the control room foreman said. “All pressures and temps returning to nominal. Both rad levels appear nominal as well. When you’ve finished cleaning up in there, c’mon out and let’s get your suits stripped.”

A two-star general in full Army dress greens stood to one side of the main control monitor. He periodically turned toward the only other formally suited individual in the room, said nothing, and returned his fascinated gaze to the monitor.

“And they’re fine?” General Dickerson asked in disbelief, turning to again face the man in the suit.

“Forty five minutes at a continuous radiation density of seven hundred rems per cubic meter per second. Under normal circumstances both men would have received fatal doses within the first thirty seconds, passed out within three minutes, and have been sludge piles within a half-hour.” Ingraham was dressed for the demonstration in full corporate regalia – dark blue suit, red silk tie, and custom-tailored white shirt. “As you can see, General, they are both fine, fully functional, and did not require so much as a respirator to effect the repairs. Had it been necessary, they could have continued working in there indefinitely, limited by nothing more serious than the need to come out for lunch or a bathroom break.”

Benjamin Ingraham was President of Hapticon Industries, a small chemical process company that had, one year earlier, come across a big idea, almost completely by accident. Hapticon at that time had been known as Aztek Chemical, a fifty million dollar low-growth firm engaged in the entirely banal business of selling catalytic chemicals to oil giants for use in their petrochemical refining processes. Then had come the annual conference of The Association of Process Industry Chemists, a gathering of six hundred of the least adventurous individuals one would imagine encountering. Ingraham, then Aztek’s Vice President of Product Development had attended the conference for three reasons, a) because it was held in Las Vegas, b) because all expenses were paid by Aztek, and c) because he had heard through the grapevine that Katelyn Travors, an old college friend, would be in attendance. The conference had been well attended, so much so that several of the more popular seminars had been over-subscribed, including the one most relevant to Ingraham’s profession – what should have been an hour and a half on the use of new catalytic compounds in petroleum regasification processes. But it had filled up too quickly, and so Ingraham had chosen, as a more or less random alternative, to sit in on a presentation entitled Potential Applications of Extremophile Micro-organisms, a talk he selected because he needed to kill two hours before meeting Katelyn for dinner, and because he had absolutely no idea what the title meant.

About halfway through the presentation though a mental light had come on and he had emerged from the meeting with about five pages of quickly scrawled notes. The talk was given by a biologist from The Rockefeller Institute, who explained that extremophile was a term coined to identify a class of newly discovered micro-organisms that against all odds not only survived, but thrived in the world’s most hostile environments. These organisms had been discovered living beneath hundreds of meters of Arctic ice, inside of solid rock, in areas with enormously high radiation levels, and even in active lava flows. No one yet understood how they managed their amazing feats of survival, but the existence and the unique talents of these microorganisms was beyond dispute. Ingraham had wondered if it might be possible to somehow harness the resistive capabilities of these creatures in a way that would benefit humans, and Aztek in the process. Nine months later, Aztek had a prototype process ready for testing, and had restructured the company, spinning off the new business unit and renaming it Hapticon, a word derived from the Greek word haptika – to touch.

“Do they remove the coating after every job?” General Dickerson asked as Ingraham guided him toward the glass door through which the two workers would shortly emerge.

“In this case, yes, but only because it’s a one-off repair,” Ingraham replied. “In most cases though, a suit can be worn for up to a month without retreating.”

“And how does the removal process work?” the General continued. As he looked through the glass door, he could now see the two workers approaching from about fifty feet away, walking slowly down a stainless steel and glass corridor. Both were totally nude except for what appeared to be scuba regulators in their mouths. Their skin bore a subtle greenish hue, barely discernible from more than thirty feet away.

“Almost a complete reverse of the application process you saw earlier,” Ingraham answered. As he and the general watched, the two workers stopped at a spot in the corridor between a pair of stripes marked on the floor. No sooner had they both planted their feet inside the two-foot diameter painted circles when glass doors slid closed behind and ahead of them, enclosing the men inside a small transparent cubicle ten feet long and four feet wide. A moment later they disappeared from view as dozens of jets in the walls and ceiling immersed them in a deluge of high-velocity spray.

“It’s an enzyme solution that the organisms don’t much care for,” Ingraham explained. “Kills them instantly in fact.”

“And the respirators?” Dickerson inquired.

“Same enzyme, but in aerosol form. Kills the internal coating – lungs, sinuses, esophagus.” As they talked, the showering process ended, and the forward glass door slid open, the naked men stepping forward another few feet before turning into a side doorway to dry themselves and get clothes.

Two hours earlier, the men had, as Ingraham indicated, undergone almost exactly the opposite process, walking naked through the showering stall, wearing identical looking respirators. At that time though, when they emerged from the shower their skins had been transformed from normal to the light green tint that had just now been washed off.

“How thick is the coating?” Dickerson asked.

“It’s similar to a light application of spray paint on your arm,” Ingraham replied. “A little slick and rubbery to the touch, but nothing you can’t get used to pretty quickly. Imagine a thin coat of Jello on your skin, and you’d be pretty close. It’s actually quite a subtle sensation, which is why we included the colored dyes, just so we can be certain who’s on and who’s off. We used a different color dye for each suit. Anti-radiation is green, anti-cold is blue, anti-heat is red, and anti-chemical is yellow.”

“Any difference in the processes from one suit to the next?” Dickerson asked.

Ingraham pulled open a side door and the two reactor workers entered, clothed in new blue denim jumpsuits. Their skin looked entirely normal. “Only differences are the coating compounds and the removal enzymes. With a quick flush, you can even use the same application portal for all four products.” Ingraham gestured toward the two men. “General, Wayne Patterson and Ralph Bellamy.”

“Pretty impressive stuff,” the general said, extending his hand in Patterson’s direction. “How do you boys feel?”

“A little thirsty, sir. But other than that, walk in the park.”

“It’s the enzyme in the respirators,” Ingraham added. “Throat gets a good chemical scrubbing, taking a bit of the mucous coating with it – leaves you a little parched, I’m afraid. It’s about the only side effect we’ve come up with so far.” The men turned away from Dickerson and Ingraham to talk with the control room foreman.

“What about regular showers, swimming, that sort of thing? No danger of the coating washing off?” the general asked.

“Nothing affects it except for the enzyme bath,” Ingraham responded. “So long as the coating’s not perforated – by, say, a cut or bullet wound – they’re fully protected.”

“How much are you prepared to share about the technical side of what’s happening here?” Dickerson probed. He had spent the past two hours seeing the anti-radiation suit in action, but still had very little understanding of the technical aspects of what he had witnessed. Ingraham led the general out of the control room and up a flight of stairs to a small conference room, spartan but for two chairs and a table on which lay a plain brown folder.

“Have a seat, sir,” Ingraham offered, taking the other himself. “Bridgestone Nuclear Power Facility is one of four nuke plants operated by Edgewater Energy. Once the company saw the demo you just witnessed, they, as you can well imagine, jumped at the opportunity to work with us as a beta test site. We have been working with Patterson and Belamy, the two technicians you met, and four others here for a little over six weeks now – all well-compensated volunteers, of course.”

“The reason I invited you here is that the military applications of our technology are, I believe, more than apparent to anyone with a modicum of vision. The product you just saw, what we call hapticol/r – r as in radiation – is ready to roll. It is, without getting into the gory details, a synthesized emulsion of radiation-resistant microorganisms, blended with various highly elastic polymers to ensure that it bonds to the skin thoroughly. Since the coating cannot be porous and still provide complete radiation shielding, we’ve also built into each compound an oxidizing agent that chemically transfers oxygen from the air through the coating to the skin.”

“How high have you tested it so far?” Dickerson asked, opening the cover of the folder.

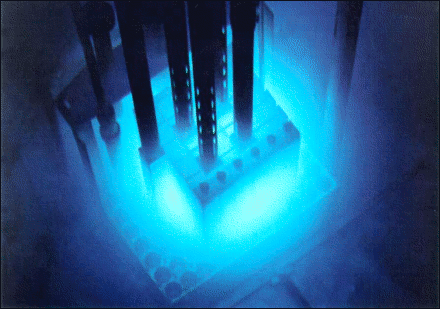

“We’ve had it up to a density of ninety thousand rems per cubic meter, with absolutely no penetration. That means, sir, that if we gave a man a scuba regulator, he could go diving inside a live nuclear reactor core without any ill effects.”

“Except for the water temperature, of course,” Dickerson countered.

“Which is an excellent segue into an overview of everything we’ve developed to date.” Ingraham said. “If you take a look at that first page, you’ll see summary descriptions of the four products we’ve prototyped so far. These protect against external hostile environments of cold, heat, radiation, and chemical contamination. The upper threat limits are listed in each case. For every hapticol product, the protection is both external and internal. They all require the same thirty seconds of external shower application, and two minutes of time on the aerosol respirator for internal coating. And let me add, general, these are cascadable products. Any combination of the four suits is possible. Order of application is absolutely irrelevant.”

“Jesus…” Dickerson said as he scanned the tolerance list for heat and cold, “do you realize–”

“What I realize, General, is that our technology eliminates the need for any special-purpose garments worn today whose purpose is protection against environmental elements. That means, scuba suits, chemical warfare protection, radiation shields. General, it almost means we’ve rendered space suits obsolete.”

“Almost?”

“As it is, we can make them a great deal thinner and closer fitting. You don’t need radiation shielding or thermal protection. There are though still issues with projectile protection and zero atmospheric pressure – that and having to breath of course. Still, we’re talking about a new spacesuit that’s no more cumbersome to wear than a wet suit and diving regulator are now.”

“Minus one twenty for the cold suit?” Dickerson asked incredulously.

“With hapticol/c you can sunbathe in the Antarctic in February if you are into that sort of thing,” Ingraham said effusively.

“Mr. Ingraham, I am a firm believer in the no-free-lunch theory of product development. Where is the downside to what you’re telling me?”

“Well, there is some cost, of course. The application/removal bay is nothing but a slightly modified piece of Level Four biological containment equipment – about a hundred grand worth. And the compounds, in quantity, will run you maybe three hundred bucks per person per application. One coating’s good for about a month. Only you can decide whether that adds up to a good deal or not.”

Dickerson didn’t need a calculator to understand the benefits of soldiers who could work in their shirtsleeves in chemically contaminated forward areas, walk unscathed through seven-hundred-degree fires, and repair radiation damage on ships and submarines without protective garments.

“God damn it, Ingraham,” Dickerson said, rising from his seat, “I’ve got half a mind to nationalize your ass right here on the spot. How many people know about this?”

“Probably more than you’d care to hear, sir. I’ve got about forty-five scientists on staff here, all sworn to secrecy of course. Still, you know what they say about loose lips. You are, though, the first potential full-scale client we have spoken with. I’m sure you will agree with the wisdom of that decision on our part.”

It took less than one week for the Pentagon to strike a deal with Hapticon for exclusive rights to the hapticol product line. Within three months, application/removal booths were in place at more than sixty percent of the military installations across the country. By nine months from the initial meeting, over two hundred thousand members of the U.S. military were regularly using one or more of the hapticol coatings, either as a feature of their day-to-day jobs, or as part of training for potentially hazardous combat conditions in the future. The Pentagon was thrilled, and was funding Hapticon’s follow-up research at a feverish rate. Soon there would be specialized coatings that could protect aircraft, tanks, and nearly every conceivable piece of military hardware.

And then, almost exactly a year to the day after the original meeting between Ingraham and Dickerson, Wayne Patterson dissolved. There was really no other way to describe it. There were no advance signs of trouble. All of Hapticon’s regular suit users were carefully examined by the company’s medical staff at least weekly. Patterson had been one of the original prototype users, and had gone through twenty-six hapticol applications and removals since the start of the program. The first and only sign of trouble came immediately upon his exit from the enzyme showering booth after an extended period wearing the hapticol/c chemical protection suit. He had taken just three steps outside the suit removal booth when his nude body collapsed, without so much as a sound, onto the grated floor of the glass and steel corridor.

What actually happened inside the man’s body was utterly beyond the capabilities of the Hapticon medical staff to understand or in any way ameliorate. From the time he fell until he was dead was less than three hours. Mercifully, Patterson was not conscious at any time from his initial collapse to the final pronunciation of death. An autopsy was immediately undertaken, with strictest secrecy and using only internal company physicians. During the process it was discovered that the now necrotic internal organs and tissue were in no way slowing the process that was taking place within the dead engineer’s body.

Unused to the sorts of physical trauma commonly encountered in an emergency room, and inexperienced in the handling of such matters, Bruce Petingill, the company doctor, approached the autopsy process in a decidedly tenuous state of mind. What he found on the other side of his initial navel-to-sternum incision caused him to quickly excuse himself from the examination room and not reappear for a full ten minutes, looking a noticeable shade whiter when he did. The first thing he found upon his return to the lab was that, rather than the well defined assortment of digestive, respiratory, and circulatory organs he had last seen in medical school, there was, instead, a more or less homogeneous mass of organic sludge. Also bizarre, and only slightly less unnerving, was the fact that the mass of dissolved internal organs was not quite of the coloration one normally associates with extreme internal injury. The hues varied from one area of Patterson’s viscera to the next, but it was immediately apparent to the doctor, and to Ingraham, who was remotely viewing the procedure, that the coloration was consistent with the yellow, red, blue, and green identification tints that had been engineered into the hapticol coating products.

Preliminary microscopic examination of samples revealed the disturbing fact that, despite the nearly twelve hours since Patterson’s death, the microorganisms that had so profoundly taken over the man’s body were still busily consuming the remaining tissue. After less than an hour of examination, Ingraham called down to the medical lab, asked Petingill to cover the body, seal the lab, and meet him upstairs for a discussion.

“God damn it, Ben. That looks like the worst case of hemorrhagic fever in history, or…” Petingill was visibly shaken, and couldn’t bring himself to sit down, pacing aimlessly around Ingraham’s large office. “I think you’d better get your Pentagon friend on the phone and tell him—“

“Tell him what exactly?” Ingraham interrupted, sitting calmly in his office chair. “We have no earthly idea what happened to Patterson yet. And until we do, I think it prudent that we not only keep this to ourselves, but that you also get to the bottom of what happened as fast as you possibly can.”

“Ben, there is no way that I am equipped to investigate…that,” he said, turning his head in the general direction of the lab. “You need a virologist – someone from CDC. And a hell of a lot better analytical equipment than we have in the lab right now.”

“You make a list of what you need and I’ll get it here. But no new people. You figure it out – you and your team. We’ve got a dozen molecular biologists in this building – all of the people who designed the hapticol products. If – and only if – you decide that this is somehow directly related to the hapticol organisms, you come to me and I’ll assign whoever we need from the design staff to work with you on getting this figured out. Dickerson is back here in ten days for an on-site inspection meeting before they release our next tranche of research funds. And until you come back with something definitive, the discussion stays in this room. Are we clear on that?”

“Ben…Jesus,” Petingill managed, “half a dozen guys saw Patterson fall in the application stall, and they sure as hell know he hasn’t been back to work today. Everybody in the place knows about this by now. What’s the story for them?”

Ingraham paused for a moment. “Patterson’s been working too hard lately. He passed out, and he’s been sent home for a few days of R&R until he gets his strength back. Meanwhile, you’ll have some answers shortly, and we’ll figure out next steps once we know what in the hell we’re dealing with.”

“Ben, you’ve got almost a quarter of a million GI’s out there working with this stuff every day. If there’s something—“

“I know damned well what we’ve got out there!” Ingraham said, louder than he’d intended. “Look, Bruce, there’s no point in raising a lot of alarms until we know what it is we’re talking about. You come back with something supportable and I will do whatever needs to be done. Trust me on that…and keep me posted on your progress,” he added peremptorily, picking up his phone handset to indicate that the discussion was finished.

It was by now past six on Friday afternoon. Petingill’s support staff, one doctor and two interns, were not especially amused to learn that they’d be working through the weekend, but at least he didn’t push them to come in until early Saturday morning. He decided to take the evening off as well and join the rest of the crew early the next day. By the time they arrived at seven the following morning, blotches of blue, yellow, and green were clearly visible on a large portion of Patterson’s skin. The organisms working away inside continued to be undaunted by the fact that their host body was now long-deceased. At the current rate of…consumption, Petingill supposed was the right word…Patterson’s body would be gone by sometime on Sunday, replaced by nothing but a pile of whatever was doing this.

Petingill and his team spent the morning taking samples from various areas of Patterson’s remains. Once they had put a couple dozen samples into glass vials – distinct only in the subtle differences in their coloration and the arcane notations on each vial’s label – they began to look more closely at what was happening at the microscopic level. After just forty-five minutes of this examination, Petingill reached for his cell phone and placed the call to Ingraham that he’d known from the outset he’d be making. Ingraham assured the doctor that one of the senior hapticol scientists would be at the medical lab no later than one that afternoon. Hanging up the phone, Petingill called a halt to his team’s activities and suggested they break for lunch until the biology expert showed up. They had agreed on Ron’s Burger Barn and were walking out of the lab just about the time that Ralph Bellamy’s wife found him in the backyard lying next to his still-running lawnmower.

By six o’clock Sunday morning Bellamy too was dead, and his body was lying on a stainless steel table in the Hapticon medical facility, next to the six-foot-long collection of organic material that had been Patterson. News of Bellamy’s collapse had not made its way to Petingill until nearly dinnertime on Saturday, Bellamy having been taken to Berrington General Medical Emergency Room following the collapse. It had occurred to no one to contact the company until Bellamy’s wife, in a fit of hysterics, had talked with her best friend, Ruth Frenzen, whose husband happened also to work for Hapticon. By the time two more casual conversations had taken place, Bellamy had been dead for two hours. The hospital had had no clue as to cause of death, other than some unspecified massive internal trauma. Within an hour, Petingill had showed up at the hospital, claiming to be Bellamy’s physician. He had insisted that the body be taken to the Hapticon medical lab, and the wife, utterly distraught, was fortunately too sedated to put up much resistance. Still, after all was said and done, the body was there, in the lab, ready for examination on Sunday morning.

Which was a hell of a good thing, since there was by now nothing at all left of Wayne Patterson to examine. The level of consumptive activity the team had been observing for the past two days had only begun abating when the availability of still-uncontaminated tissue had diminished. The examination of Saturday afternoon – before news of Bellamy’s collapse had reached anyone at Hapticon – had revealed one important and now indisputable fact – a fact that had been nearly obvious from the outset to anyone objective enough to listen. The invaders that had so rapidly and completely consumed Wayne Patterson and, now apparently, Roger Bellamy, were indeed the hapticol organisms. In fact, it was discovered that representatives from each of the organism families to which each man had been exposed during the testing were present in large quantities. The relative density of each organism though was a function of which part of each man’s body the sample was taken from. Both Bellamy and Patterson had, at one time or another in the past year, been exposed multiple times to all four of the current hapticol products. Without yet having a great deal of scientific data to prove the hypothesis, it was looking as though the organisms had been engaged in a sort-of competition within the men’s bodies to lay claim to more of the tissue than the other organisms – rather like an internal four-way tug-of-war.

“That leads to at least two really disturbing conclusions,” Petingill said, standing back in Ingraham’s office along with Tricia Boden, the microbiologist assigned to work with the medical team. First, the organisms are not being completely eradicated by the enzyme bath we’ve been using after each application – at least not the internal ones. And, more importantly, these organisms are not the benign little critters we thought they were viz a viz the human body.”

“But the enzyme compound is fatal to the organisms,” Ingraham said. He was slouching in a huge leather chair, his arms splayed on the chair’s arms, his head tilted resignedly to one side. “It’s one hundred percent lethal – one goddamn hundred percent!” he shouted to no one in particular. “Jesus, this thing was tested every way from Sunday – six damn months before we started using it on humans. How in the hell…”

“Ben,” said Tricia, sitting down on the coffee table, “it’s going to take a while yet to figure out the mechanism. I’m going to venture an opinion though. These things are survivors – that’s why we picked them to work with in the first place, right? The stripping enzymes work fine, but only if the compound actually gets to the organisms. I think that somehow these things have learned how to avoid the enzyme, and there’s only one way that can happen. They’re burrowing in from the inside – into, below, the mucus layer of the esophagus and sinuses. We’ve assumed a surface coating that remains on the surface, but mucus is an excellent barrier against all sorts of contaminants – that’s what God put it there for in the first place. If the organisms get underneath, that’s it, they’re in.”

Ingraham sat forward in the chair, cracking his neck to each side. He was showing relatively remarkable composure for a man whose company’s future was evaporating before his eyes. “So this is the sort of thing that would happen only after multiple exposures?”

“Don’t know yet,” Tricia replied. “Worst case is that all it takes is one. These things are asexual, self-replicating. If even one gets past the stripper and survives, that’s enough. In a way it’s odd that this took as long as it did. The average replication period on the four organisms is under an hour. Either you’re right and it does take multiple applications – a build-up of some sort, or they’re going into some sort of dormancy for a long time and then emerging in response to an external trigger we don’t understand.”

“But the two guys, succumbing so close to each other,” Ingraham countered. “They began the applications on the same day last year. What in the hell would make them react a year later, within forty-eight hours of each other?”

“We can’t answer that one either,” Petingill responded, “but I can tell you a few things that need to happen right now. The applications here in the lab have to stop for the moment. Everyone who’s suited should get a scrub – maybe two scrubs. Then everyone who’s ever used one or more hapticols gets a thorough internal assay to search for traces of the organisms. Assuming that we do find some, that will allow us to correlate frequency of usage with contamination levels. There’ve gotta be, what, at least twenty-five guys just on our premises that are regular applicants.”

“Twenty nine, actually,” Ingraham confirmed, “and I think you’re right. We also need a hell of a good story to keep these people from freaking out.”

“You’ve got a much bigger problem than that to deal with though,” Petingill added, raising the other obvious issue no one else had yet said out loud. “You need to get the military applications to stand down, at least until we get to the bottom of what we’re dealing with.” Ingraham only nodded his head in silence.

“And Ben,” Tricia said, after an uncomfortably long pause, “there’s another thing.”

“How can it possibly get any worse,” Ingraham replied, a wry smile on his face.

“You…we…need to be prepared for the possible worst case scenario here.”

“What in the hell are you talking about?” Ingraham said. “The worst case scenario is that this kills a significant number of our users, and we not only lose this company, but cause hundreds or maybe thousands of fatalities. Oh, and if I’m really lucky, I might get my ass thrown in jail to boot.”

“Actually, no, that isn’t even close to worst case,” Petingill said. “Worst case A is that we determine this to be unstoppable and fatal in every user, even single-usage wearers. Keep in mind, these things are not going to go down without a fight. They are, by definition, the best survivors on earth. But worst case B – that’s the scary one…” He paused. “We know that the organisms are hostile to humans, if we’re lucky, hostile only in heavy doses, but hostile nevertheless. We believe that they survive by getting below the internal mucus layer, which means that at any given time, some of them are actually within the mucus layer itself. Well, that’s where stuff comes from when people sneeze and cough.”

“Meaning?” Ingraham asked, fearing he already knew the answer.

“Meaning that this thing may be contagious – airborne contagious. And if you combine that with a high or very high fatality rate, then throw into the mix the fact that we’ve already got more than two hundred thousand GI’s in a couple of dozen countries who’ve been regular users for many months. Well, Ben…that is some serious shit at that point.”

No one said anything for several seconds. Then Ingraham rose from his seat and walked to the office window. Without turning around he said to the window, “We can corroborate or eliminate that theory by testing all of the people here in the building who have not been users, but who regularly interact with those who are. Basically that means everybody in the company, starting with yours truly.”

“Uh…okay,” Petingill agreed. “First step is to come up with a way of getting internal – deep internal – tissue samples from folks. Throat scrapes aren’t going to do the job with this. We’ll need a fiberscope and some way of doing a deep mucus sample down in the esophagus and the lungs. Then we’ve got to queue these guys up – first the users, then…”

Petingill’s voice gradually faded away as Ingraham continued gazing absently out his office window, past the field, and into the woods behind the company headquarters building. He had never personally donned a hapticol suit. They’d talked about it – good morale booster for the guys – that sort of thing. But in the end it was up to the working stiffs to take the real risks, wasn’t it? For sure, General Dickerson had never walked into a hapticol booth. He’d stood by and watched as his men did it though. Probably shaken a lot of hands, kudos for being a trailblazer, another giant leap for your country.

Ingraham turned from the window and, still in a daze, made some agreeable comment before sending Petingill and Tricia back to the lab to do whatever needed doing. With a quiet thud, the heavy office door swung closed and Ingraham let himself drop into the large brown leather chair behind the desk. He sat utterly motionless for several minutes before pushing the intercom button on his phone.

“Beth, get me General Dickerson at the Pentagon please.”

Releasing the button, he leaned back again in his chair, staring for a moment up at the ceiling, whose intricate moldings he had never really noticed before. The trophies in his bookcase, symbols of the competitive drive that had gotten him into this office in the first place. The diplomas and certificates that hung on the wall above the sofa, testament to his intellect and hard work. Eventually his eyes fell to his desk and the eight-by-ten photo of his wife and two daughters, each of whom he’d kissed goodbye that morning and nearly every morning that he could remember. When the phone finally rang two minutes later, he was still examining, through fear-glazed eyes, as many details of the office as he could find, anything to keep from looking down at the small blue stain on the back of his left hand.